“Be very careful and make sure to not touch anything at all,” I hear a whisper in the pitch dark room. It’s not everyday that I find myself in a situation like this one — with whisperers guiding my next move. But then again, it’s not everyday that I find myself inside the hunting room of the Maharaja at the Mysuru Palace.

I flinch as the lights come on, only to open my eyes and see years of legacy preserved in a single room, unfold in front of me. Upon entering the palace I, like the others, was hoping to read the history of the Wodeyars and their continuing legacy. Little did I know that my ‘special’ guide and a certain left turn would take me to a room reserved only for a select few.?

Rebuilt over the years, the Palace’s first construction dates back to the 14th century. What now touches the city skyline was designed by the British architect Henry Irwin — in Indo-Saracenic style — constructed in 1912, and is the fourth structure to occupy this site. As I continued to marvel at the structure and its intricate designs and patterns, I was told that there awaits a surprise for me later that evening.

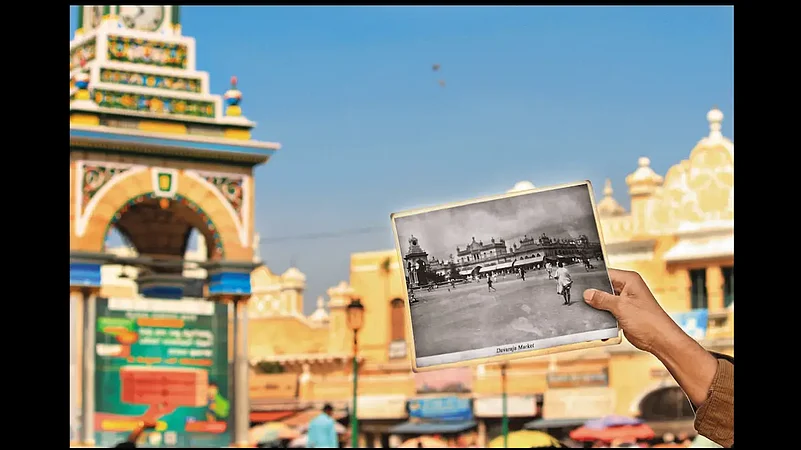

Come to think of it, Mysuru is a very warm city, right from its weather to the people and even the colour of most buildings — a faint yellow. And following this trail of yellow I made my next pit stop — the Devaraja Market. Dating back to the reign of Tipu Sultan, this market remains historically and culturally significant. What was a weekly market back then, is now a full fledged daily affair and a locals’ regular go to place. From fresh flowers, to fruits and clothes, you name it and you find it. As I paved my way through the dingy lanes of the market, photographers — both amateurs and professionals were a common sight.

Another structure that one cannot miss here is the clock tower. Earlier used as a platform to make all necessary announcements, local hawkers, afternoon nappers and some local folk cherishing the legendary Mysore pak encroach the space now. Coming to the Mysore pak, it is at the beginning of the Devaraja Market that you will find the original makers of the sweet. An accidental discovery in the royal kitchen, the Mysore pak’s legacy continues at a humble corner shop — the Guru Sweet Mart, adjacent to the market’s entrance. However, the royal secret recipe was shared (or maybe discovered) and across the street you will also find Bombay Tiffanys and a motley crowd trying to make their way inside the shop.

As the day progressed and the temperature sored, my naive mind thought it was going to be a sluggish afternoon. But it only took a few minutes for Sachin — the showman from Gully Tours — to shake me out of the slumber and show me the ‘hidden Mysuru’.?

The secret behind these convoluted knots is Arun Yogiraj’s legacy, skills and craftsmanship. Hailing from a family of sculptors, it was Arun’s grandfather — B. Basavanna Shilpi, a recognised artist of the palace — whose deft hands at work grabbed his grandson’s attention to the art form. Using his grandfather’s designs — done and tactfully preserved on paper — as references Arun has delivered life-size white marble sculptures of Dr B. R. Ambedkar, Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa as well as that of Maharaja Jayachamarajendra Wodeyar (which was a whopping 14.5 ft). Working out of his home-cum-workshop, Arun calls his home his first school. “My father and grandfather wanted to keep every stone alive, their every stroke on furlough made an impression on me,” he says shyly. No wonder he’s called Mysuru’s modern architect.

A short drive away awaited another wonder in the form of a minute yet completely spellbinding art form — inlay in wood. The rulers of Mysuru — the Wodeyars — patronised this art form, which is well reflected within the confines of the Palace. Rosewood is used for creating most of the finished products, however various kinds can be resorted to — such as jackfruit, champa, etc — depending upon the texture and the colour required. If some records are to be believed, rosewood inlay dates back to nearly 400 years.

While I was trying to not stumble upon various logs of wood and tools around the dimly lit workshop, I was acquainted with the rather long and tedious process of creating a single artwork. The process starts with a detailed sketch of the product — with dimensions and colours clearly indicated. The artisan then cuts out the figures by placing them on various wood pieces. Later, small depressions are made on the base to fit the cutout designs. The interwoven pieces of wood are then placed on the surface, nailed together and flattened by running them through a mechanical press. Post this, they? are polished several times to give them the lustrous finish we see them in.

Before I realised, the sun had made its way to the horizon and was now partly visible, colouring the whole city into hues of faint orange and pink, complimenting the existing yellow. Although exhausted after the long day, I was still anticipating my surprise as we moved in the direction of the Palace again.

To engage your taste buds, move over the famed Mysore masala dosa and give the Mylari dosa a try. Extremely soft and flavourful, it is served with dollops of butter.

It was only a matter of split seconds — the sun drowned quickly, the moon rose swiftly and a thousand incandescent bulbs lit up on the surface of the Palace. My eyes glimmered, partly because of the light from the bulbs and at the sheer magnificence of the Palace post sundown. With this image stamped in my head, my eyes and heart full, I retreated only to plan my next visit.

- Previous Story

Tom Holland Recalls ‘Trip Of A Lifetime' Visiting India With Girlfriend Zendaya

Tom Holland Recalls ‘Trip Of A Lifetime' Visiting India With Girlfriend Zendaya - Next Story