Tapasya—a spiritual discipline that involves deep meditation, austerity, restraint and efforts for self-liberation—holds great relevance in the Indian mythoverse. It refers to practising rigorous penance and aiming for miraculous returns. Those who performed tapasya chased divine secrets, which manifested in the form of momentous knowledge for sages and celestial astras (weapons) for warriors. Every kind of tapasya demands great sacrifices and hardships. The path to spiritual transformation is paved depending upon what one seeks to achieve. The results inspire masses rather than affecting just one.

Women In Ramayana: Tapasya Of Epic Change-Makers

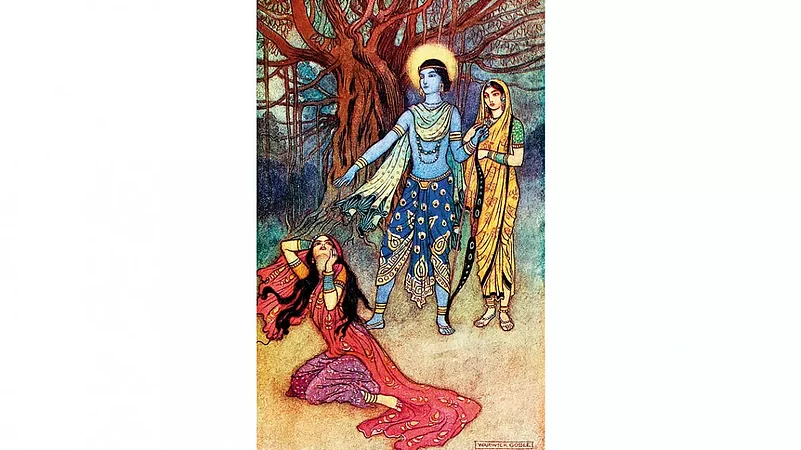

Women in the Ramayana inspire fascinating leadership trends

Indian philosophy proposes that tapasya is a conscious choice for all leaders. It is a personal investment for social resurrection. It is motivation and training, both!

While popular narratives have viewed tapasya in the form of predominantly male fancy, women’s culture in Indian epics reflect upon it as brave contemplations by fierce change-makers. The Ramayana (and also the Mahabharata) shows an interesting trajectory of feminine leadership with abundant kindness, progressive decision-making, constructive protests and furious fights. No leadership sustains only on the pillars of virtues. The women make ‘mistakes’ as does everyone. Owning up the failures leads to their tapasya.

Sita’s Tapasya

Sita comes across as a visionary who is not afraid to take risks. She is a loving soul, longing for the company of her husband, which adds to her tendency of romancing risks! It shows in her decision of moving to the forest when Rama is exiled. Her risk-taking nature comes back when she sends her husband to chase a golden deer; when she sends her brother-in-law Lakshman to find Rama; and, when she does not hesitate to go near Ravana—disguised as a sage—seeking bhiksha (alms). Her decisions go wrong though; she gets kidnapped. With this development, Sita turns into a tapasvi for life. The prisoner of Lanka performs austere penance, refusing the horrific Ravana or his colossal properties from influencing her mind—so what if her body has been dragged into the country? Nothing about Ravana can ‘touch’ her. Her suffering does not make her risk-averse. When Hanuman comes to Lanka and offers to carry her back to Rama, she ref-uses the favour. Yet another leadership idealism which believes even in the face of adversity that deception is Ravana’s trait; it is not for her to hide and run. This decision marks her growth from a woman with innocent excitement to the future-queen now representing her country, unwilling to bow before fears and waiting to witness a befitting punishment of the enemy who has crossed both moral and geographical boundaries.

While in Lanka, Sita is only an individual. Once back in Ayo-dhya, she would be a queen—an entity, a chair and a public persona. Responsibilities will be more severe; work will be rather thankless; and, mistakes will have amplified repercussions. Is Sita prepared? The fire test seems like a symbolic intimation suggesting that her real struggle begins post her exit from Lanka. The queen of Ayodhya continues as a tapasvi at heart, duly fulfilling her duties and prioritising people over self. But she finally removes herself from public glare when she believes that they do not deserve her patience. With Sita’s withdrawal, the Ramayana ends—nothing more is left in the story—just like a significant era ends with the resi-g-ning, retiring or death of every great leader.

Kaikeyi’s Tapasya

A warrior by temperament and a queen by designation, the second wife of King Dasharatha is courageous, skilled and enigmatic—the ability of independent thinking being her biggest strength. Like most warriors, she is an ambitious taskmaster and gets her commands executed at sword-point. This political strategist is unhesitant about communicating her needs with clarity and carries lawful evidence of her rights. She is also deft at using her beauty and talent relevantly, playing them to her advantage. The quest for power is Kaikeyi’s tapasya.

Following the law of duality, the ‘giver’ queen, who once saved the king’s life on the battlefield, becomes infamous as a cruel ‘taker’—when a very emotional Dasharatha falls to death after exiling son Rama upon the insistence of Kaikeyi. The demand for exiling Rama may have resulted from the fact that she is more competent than the other men and women of her times. Obviously, she cannot be bossed over by the undeserving. And she did not consider Rama deserving!

The traditional school believes that Kaikeyi could not retain her balance when it was her time to give away the reins of power to the next generation. She grew insecure. Modern times have witnessed many such occasions when great businesses have collapsed because mighty leaders refused to vacate their seats, turning away from meritorious successors, resulting in a growth-stagnancy and eventual downfall.

However, had Kaikeyi not objected to Rama’s crowning, the Ramayana would not have unfolded, celebrating the valour of the Ayodhya prince and the resilience of his wife. This drives home the learning that outstanding leaders cause bigger turmoil, but the grander the disaster, the larger are the opportunities that come with revival. Kaikeyi’s role in the Ramayana is perhaps that of the soil-churner with a pointed plough, hitting hard, but enhancing fertility in the process.

Surpanakha’s Tapasya

The pampered princess of Lanka, and beloved sister of Ravana, has grown up in a high-energy environment that desires unlimited expansion, even if ethics and righteousness have to be compromised. Modern leaders might call it a profit-maximisation mindset. Under such mindsets, everyone who comes in the path of a dream must be eliminated to continue with the chase. Ego and anger rule, the virtues of compromising, renouncing or forgiving are read as foolishness! Revenge is Surpanakha’s tapasya. Her decision is one of the most interesting and devastating ones in the mythical leadership theories.

It begins with Ravana killing his enemy and Surpanakha’s lover, Vidyutjibha (husband, as per some texts). An angry Surpanakha disappears from Lanka, only to make her presence felt in Dandakaranya forest, where Rama, Lakshmana and Sita have settled during their exile. Surpanakha approaches Rama first and then Lakshmana, proposing marriage. Both brothers decline. Surpanakha feels insulted. She attacks Sita, the seemingly weaker one among the three people before her. Lakshmana raises his sword and slashes her nose, adding injury to insult.

Standing between Rama on one side and Ravana on the other, both of whom have caused her pain, Surpanakha takes a tremendous strategic call which seals her intelligence as a politician. She decides to outsource her war! Going back to Ravana, she orchestrates a series of events, allowing the two great warriors to take the centre stage and fight a ruthless battle. As a part of her game, Rama is returned to agony caused by his separation from Sita. No stones are left unturned to provoke Ravana, who is consumed into the passion of winning instead of following the fair path as a leader.Surpanakha’s tapasya does not yield positive results for herself, but her society attains moksha (liberation) from the grips of an arrogant king who has messed up everything in spite of his multi-faceted brilliance in art, science and ayurveda. Her story highlights a violent protest, fearless and careless about the repercussions, turning the tables in history and forcing the observers to take notice—a humiliated woman can be dangerous!

Women in the Ramayana exhibit a fascinating trend. Their participation initiates a Karmic cycle that induces punishments or rewards, depending upon the scale of the offence or goodness. With Surpanakha’s uprising, Rama suffers separation from Sita. Ravana loses it all. Kaikeyi ensures that Rama takes over Ayodhya when he is bigger and better, having inscribed himself on a wider map—thus scripting renewed progress for her country. Sita is effortless while evolving others in her company. Her presence in Lanka ushers in a striking disturbance in the stability of the land by affecting interpersonal relationships. In a country where Ravana is supreme, Trijata is the first rakshasi to rebel silently and stand by Sita. Ravana’s loyal wife, Mandodari, follows her path. Though she never stops loving Ravana, she does not remain his faithful supporter any longer. Next to drop out is brother, Vibhishana. Later, son Meghnad and another brother Kumbhakarna also express their contempt against the king’s decision of abducting Sita—however, they choose to fight for Ravana and die in the battleground.

While considering the stories of the Ramayana (and also the Mahabharata), we must remember that these are not commercial fiction. The stories carry deep philosophical messages. The idea of God in the ancient shastras (texts) is established as the keeper of Dharma. The women in God’s world feature as the force that triggers action, punctuating the still waters of life with a longstanding disruption. By the time the muddled waters navigate back to calmness, the ultimate learning dawns. No one is victorious on earth. Everyone has failed. Everyone has lost something that is critical for him or her. But all failures, all losses, come with a platter of secret wisdom propelling leadership. The courage to embrace this truth, unearth those secrets and attempt to heal from within is Tapasya!

(Views expressed are personal)

Koral Dasgupta has written a range of books—from academic non-fiction to relationship dramas

(This appeared?in the print as 'Tapasya Of Epic Change-Makers')

- Previous Story

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana - Next Story