Anti-caste crusader and activist, Professor Shrawan Deore, was only a young student when anti-reservation protests raged across Maharashtra in 1982. At the time, the All India Maratha Mahasangh founded by then Congress MLA, Annasaheb Patil—an eminent leader from the Mathadi community in Bombay, distinguished by his burly physique and twirled moustache—was spearheading Maratha melavas (gatherings) to oppose reservations for socially and economically backward castes. Marathas comprise nearly 30 per cent of the state’s population, and have long maintained an aristocratic, feudal and political hold in the state. From chief ministers, ministers and legislators to sugar barons, agricultural and banking co-operatives and educational institutes, Marathas were comfortable in dominance.

The Marathas' Post-Mandal 'Backward March'

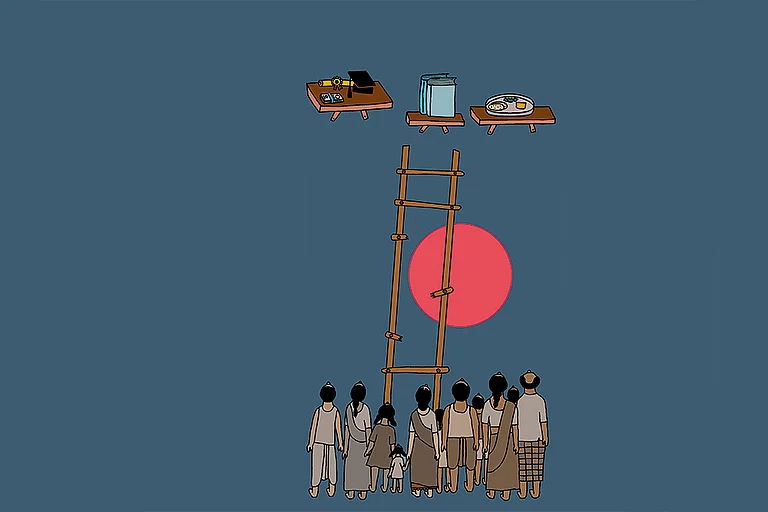

After OBCs were granted a 27 per cent quota and reservations in local self-government bodies, the Maratha agitation against reservation based on social backwardness took a U-turn

But across the country, OBC leadership was slowly taking centrestage due to the emerging phenomenon of reservation politics, recalls Deore, 65, head of the OBC Political Front party. “All the top positions in the government and the ruling class belonged to the Brahmins or the Marathas. They feared the implementation of the Mandal Commission (recommendations) would challenge the status quo by elevating the positions of the OBCs in the state and bringing them into power,” he says.

Farmers, women, students and unemployed youth used to throng meetings organised by the Maratha Mahasangh at the time, contributing to a heated atmosphere against the ‘low castes’ with disparaging slogans of ‘‘Mandal Aayog, Bandal Aayog,’’ (Mandal Commission is a bluff) and threats of ‘‘we will burn Maharashtra to ashes’’ echoing in the state’s socio-political spaces.

The Mahasangh’s provocative manifesto demanded reservations based on economic ‘backwardness’, not social ‘backwardness’.

Upon learning about a similar melava being held in his native Dhule city in northwestern Maharashtra, Deore, belonging to the Mali community, a designated OBC grouping, along with his friends from leftist organisations, hatched a plan to disrupt it. Nearly 200 people had gathered on the verandah of the famous Dagadi building in Rana Pratap Chowk, when he and others threw pamphlets calling for OBC reservation and shouted “Mandal Aayog Zindabad”, forcing the burly Patil to flee.

The incident inspired OBC activists in other parts of the state to protest such melavas with black flags. “The Mahasangh was established at the behest of the RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh) and the Jan Sangh to oppose the Mandal Commission’s recommendation of reservations for OBCs. They had spread terror and fear across the state. It became imperative for us to counter them,” recalls Deore.

Patil committed suicide the same year, becoming the first ‘martyr’ of the Maratha cause. A decade later, after OBCs were granted a 27 per cent quota and reservations in local self-government bodies, the agitation took a U-turn. The Marathas, finding their numbers significantly reduced in government institutions, village panchayats and zilla parishads, began seeking reservations for themselves under the same backward category.

The Marathas, who had always claimed a superior and prestigious social position, were now willing to step down in the caste hierarchy to garner reservations.

Manoj Jarange-Patil, an activist from Marathwada’s Jalna, is the latest leader to demand the inclusion of Marathas within the OBC category.

Presently, there are 492 OBC castes listed in Maharashtra, constituting 55 per cent of the population, and yet they avail 19 per cent of the reservations. Notably, various central and state-level commissions have rejected the inclusion of Marathas in the backward classes. In 2004, the Congress’ Sushilkumar Shinde government allowed the inclusion of the Kunbi-Maratha and Maratha-Kunbi categories in the OBC list. However, Marathas without evidence of Kunbi familial linkages remained outside the scope of reservation benefits.

In the pre-British era, American-Indian scholar Gail Omvedt notes, most of the community was simply known as Kunbis (peasants), with only the feudal aristocrats and ‘‘ninety-six families’’ (96 Kuli) recognised as Marathas.

Over time, a sharp distinction emerged between the Marathas and the Kunbis. The Marathas proudly flaunted their warrior lineage as descendants of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, the great Maratha king, while the Kunbis remained engaged in farming as land cultivators. The Marathas became wealthy landowners and feudal lords, while the Kunbis stayed poor, working as farm tillers. The Marathas often engaged in exploitative relationships and caste violence against Dalits and backward castes as rulers and village strongmen.

Manoj Jarange-Patil, a frail 42-year-old activist from Marathwada’s Jalna district, is the latest leader to demand the inclusion of the Marathas within the OBC category. Jarange-Patil has intensified the agitation against the state government, staging multiple hunger strikes and organising massive public rallies to seek recognition of the Marathas as part of their ancestral Kunbi caste, which is listed as backward.

His demand to grant Marathas reservation under the OBC category as Kunbis has stirred significant controversy. Across party lines, backward caste leaders have threatened severe consequences over the inclusion of Marathas in the OBC category, putting the state government in a conundrum over the categorisation, especially ahead of the upcoming state assembly polls.

“Historically, Marathas looked down on the Kunbis. They never considered the Kunbis as their own. They wouldn’t even sit in the same line for food with us, nor would they marry their daughters to us,” says Vishwanath Patil, a former legislator from Palghar district in Western Maharashtra and founder of Kunbi Sena, a social and political organisation for farmers’ welfare.

To appease and pacify Marathas ahead of the Lok Sabha elections, the Eknath Shinde-led BJP-Sena-NCP coalition had granted the community 10 per cent special reservation under the Socially and Economically Backward Caste (SEBC) quota in February. This was the third such Maratha quota bill after the Bombay High Court (2014) and the Supreme Court (2021) struck down the 16 per cent reservation, citing no valid grounds to exceed the 50 per cent quota ceiling. The government also decided to issue Kunbi certificates to Marathas who could provide evidence of belonging to the Kunbi caste or having Kunbi blood relatives.

Patil argues that identifying 57 lakh Marathas as Kunbis has deepened discontent among the farming community, which is already struggling to cope with climate change and land loss. He claims that within the OBC category, the Kunbis have benefitted the least from reservations and now face further marginalisation as Marathas too seek their share.

The Maratha community had the option to seek reservation under the Economically Weaker Section (EWS) quota, available to the general category, but their leaders rejected this option. The new 12 per cent Maratha reservation under the SEBC raises Maharashtra’s total reservation level to 62 per cent, exceeding the Supreme Court’s 50 per cent cap. OBC leaders call it ‘illegal’ and ‘unconstitutional,’ challenging it in the Bombay High Court and before the State Backward Classes Commission.

“The Marathas are the ruling class. Maharashtra’s politics is still dominated by dynastic families, most of whom are Marathas. If the Marathas enter the OBC reservation as Kunbis, they will hijack our reservation,” stresses Laxman Hake, OBC leader and former state backward classes member. Hake criticised the Shinde government for unconstitutionally granting Maratha reservations under the SEBC quota to secure their vote bank. He resigned from the ten-member State Backward Class Commission in December, alleging government pressure to fast-track the reservation. Hake argued that “reservations are for social justice, not economic programmes” and criticised the government for neglecting backward castes with less than one per cent of the state’s Rs. 6.12 lakh crore budget allocated for their welfare.

Jarange-Patil’s push for blanket reservation for all Marathas as Kunbis has complicated the quota issue. Leaders like Rajendra Kondhare, president of the Akhil Bharatiya Maratha Mahasangh (ABMM), believe the Maratha community should avail the benefits from the Kunbi certificates and 10 per cent SEBC reservation—until the High Court makes a final decision on the quota. “There are legal and constitutional deterrents, besides political obstructions, to include all Marathas as Kunbis. It would require 19 per cent separate reservations based on its population, which is not practical,” he says.

No party, including the ruling coalition, will commit to including Marathas in the OBC category due to potential backlash from backward castes, even as opposition parties, including the Maha Vikas Aghadi alliance and its components, the Shiv Sena and the NCP, are calling for a caste census and increasing the reservation cap beyond 50 per cent.

With state elections likely in November, Jarange-Patil plans to field Maratha candidates and urges the community to avoid mainstream parties. OBC leaders like Deore and Hake are also preparing to challenge Maratha candidates.

While the Maratha vs OBC fight threatens to upend the well-est-ablished caste-based electoral equations, the reservation question may well continue to mire the next government.

(This appeared in the print as 'Backward March')

- Previous Story

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana - Next Story