A sanitary napkin wrapped in newspaper passed on under the desk in class, group excursions to the bathroom, sly notes in secret languages, self-help groups selling crisps, shared recipes and silent kitchen solidarities. In India, friendship between women can look like many things. For 17-year-old student Anita (name changed), it took the shape of a late-night phone call to an older woman, the daughter of her father’s friend. “I skipped my period for a month after having sex with my boyfriend for the first time. I was freaking out,” Anita recalls. Despite growing up in a liberal, upper middle-class household in Delhi, Anita could not go to her feminist mother for help. “I needed a friend, another woman who would understand what I went through without judgement and tell me what to do.” Anita did not end up getting pregnant. Instead, she was diagnosed with a hormonal disorder called PCOD. But she recalls the shame she felt at the time and adds how thankful she is for having a woman she could call on to help her at a time when she couldn’t call anyone else.

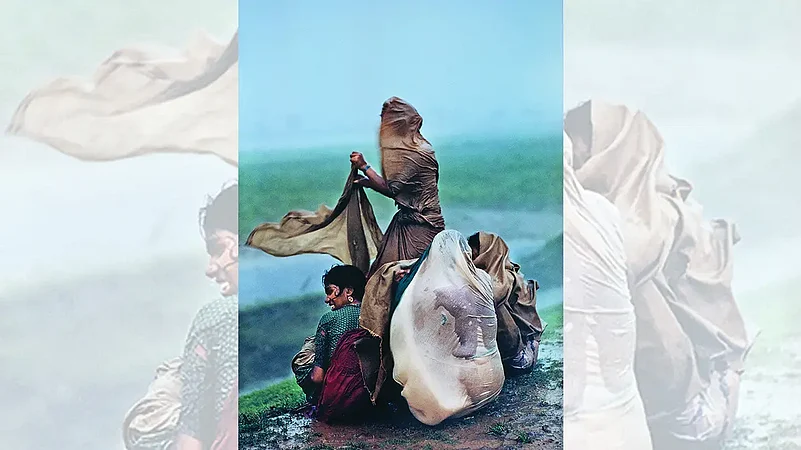

Sisterhood Of Solidarities: How Women Band Together To Fight Injustice And Oppression

In a male-dominated world that forces women to inculcate patriarchal morality and pull down other women, there are those who defy these norms through comradeship, providing a safe space for other women

Like Anita’s didi, women are often the first res-ponders to any crisis faced by other women. Be it the shared history of oppression that women in patriarchal systems across countries and cultures face or the result of an oft-enforced norm of homosocial existence, women’s solidarity grows out of the need to support each other when faced with hostile situations and common oppressors. And India, the solidarity and networking of women have helped lead several movements for the socio-economic and political upliftment of women. Yet, most Indian women grow up hearing and bel-ieving that ‘women are women’s worst enemies’,? a stereotype perpetuated by countless saas-bahu serials depicting evil mothers-in-law and fiendish vamps out to oust innocent, ‘good’ women.

Turkish feminist scholar Deniz Kandiyoti in her seminal 1988 essay Bargaining with Patriarchy spoke of the strategies employed by women to make the best of oppressive gender structures and rise through the social and familial ladder. But while pop culture widely promotes the women-hate-women trope, Professor Mary E. John, former director of the Centre for Women’s Development Studies at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, points out that such simplifications undermine the complex set of factors that actually dictate gender relations and dynamics. “Family and marriage form the fundamental blocks of the patrilineal and patriarchal society in most parts of India. These institutions are organised with the notion of a male head of the household who has some notion of power while women live in direct dependency on the male members. On the other hand, there is a continued emphasis on homosocial socialisation and enforcement of the public-private divide, which forces women to be herded together, be it in schools or at home,” John tells Outlook. “Bargaining with patriarchy was a way to say that even within such patriarchal structures, women do not simply become fear victims, always opp-ressed and subjugated. Instead, they have agency to bargain because they have something to give, be it sexual gratification, reproduction, the potential to bear male heirs, or labour,” adds John. However, despite their apparent superiority, she points out that the fact they are bargaining means they are not in a position of control.

Kavita Krishnan, secretary of the All India Progressive Women’s Association and a prominent Left leader, feels that solidarity between women plays an important role in the socio-political and economic upliftment of women. “I would not be in politics if it were it not for friendship between women and some very strong bonds of friendship that drew me into activism,” she tells Outlook. Krishnan points out that patriarchy forces women to become the custodians of patriarchal morality within the family and therefore pull down other women. “The directive to stand in opposition to women who defy patriarchal norms runs very deep and finds voice in all of us women at some point or the other. The fact that friendship and comradeship between women can provide a safe space for women to defy that strong directive is important and not often talked about,” says Krishnan. Those who enforce patriarchy are very aware of this power of female friendships and solidarity and constantly try to diminish or undermine such relations. In the 1980s, Krishnan states that there was a wave of self-help groups and micro-finance movements which developed into more expansive movements against women’s issues like domestic violence and sexual abuse. Now,? the same government or public agencies behind microfinance institutions have started to incentivise women to turn against each other in cases when one of them defaults on loan payments.

Despite such attempts, women’s solidarities find a way. During the Covid lockdown when marginalised women faced massive job loss and debt, women from microfinance movements banded together and protested; some even got their state governments or agencies to roll back the punitive measure and give more time to the women to repay their loans. Several sex workers from Telangana and West Bengal Outlook spoke to reg-arding increased debt during the lockdown, have testified to the problems they faced in repaying their debt and about the women’s efforts in buying more time and leeway for the defaulters instead of acting as loan sharks against them.

In Uttar Pradesh, women’s rights activists previously working with the now-defunct Mahila Samakhya programme narrate similar tales of solidarity networks that continue to provide aid to victims of gender violence through informal gatherings and sessions which operate even without government funding. Activists have been trying to harness the power of female friendships and networking to create constructive resistance, especially in rural India where many women facing violence or abuse lack any social structure or safety net. Since a majority of systemic abuse comes from intimate partners, relatives or family, victims often have no place to lodge their complaints or even disclose their trauma to anyone. “The need for women’s networks based on mutual trust and cooperation can be key in such situations,” says Khalid Chaudhry, regional director for Action Aid Association, which runs the ‘Adolescent Girls Network’ in UP to provide a protective and conducive environment by involving women from the community to act as watchdogs against violence faced by women. One of its members, 13-year-old Anjali, recently managed to stop the child marriage of a friend studying at her school, in Badaun. “Her family was not in her support. It was only up to some of us girls in the school to figure out what to do,” Anjali tells Outlook.

Not all women are activists and not all women’s friendships lead to movements. Women in a family may manage to form solidarity against an oppressive male or form sisterhood to affect socio-political change. But even the simplest of friendships between women can shape feminine identities by not only challenging patriarchy but the notions of kinship that Indian caste-based familial structures are based on that primarily result in cutting off women from their own families or from sources of socialisation outside of home.

Eileen Green, in her 1998 essay, outlines how even leisure sites for women often become gateways for reconstructing femininities. Green argues that phenomena like “women’s talk” can be examined as examples of “key mechanisms through which feminine subjectivities are secured”. Interaction in leisure contexts with close friends or acquaintances—such as when women interact at the common well in villages or “work-wife” chats in urban office cafeterias during lunch break—provide essential spaces for women to “review their lives” and assess their pains and satisfactions through social “mirroring”, humour, and shared tips for survival. Surabhi Yadav, who has been documenting women at leisure under ‘Project Basanti’, says, “Leisure unites women, it is a glue that can bring people, especially the oppressed, together without an agenda”. Instagram handle, which has over 17,000 followers, is a curation of photographs and stories depicting everyday women at leisure, sharing moments of privacy, selfhood and sisterhood. “Perhaps in leisure, because our guards are down, we are lighter about our human condition, which is often complex and intimidating” Surabhi muses.

Examples of the contribution of feminine friendships and solidarities toward the movements against oppression are aplenty in history. Krishnan, in her latest book, talks about the friendship between Shah Jahan Appa and Satya Rani Chaddha during the anti-dowry movement in Delhi in the 1980s, which was intrinsic to the success of the movement. Or the powerful friendship that developed between stalwarts like Savitri Bai Phule and Fatima Sheikh, which played an enormous role in the emancipation of thousands of women. Or the kinship and shared love for the forest between the women that were at the centre of the Chipko movement to save their trees. While male friendship is often eulogised in tales of valour and resistance like Bollywood’s Jai and Veeru or the legends of King Arthur and Lancelot in the West, stories of women, as usual, remain untold.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Sisterhood of Solidarities")

- Previous Story

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana - Next Story