Contagious diseases have a long history of racism linked to them. Their linkage to poverty and living conditions have also helped to deepen class prejudice. Even more damning is the naming of diseases after countries and communities. The Ebola outbreak in Africa, Asiatic flu and cholera, the bubonic plague, Middle East respiratory syndrome, have all been sufficiently racialized to lead to deep and widespread prejudice against certain groups of people. The afflictions associated with HIV-AIDS, sometimes called the “Gay Plague,” have often been imagined as divine retribution against homosexuality. Mary Mallon, a figure from 18th century England, stands as one of the most infamous instances of malicious symbolism, in her vicious incarnation as “Typhoid Mary.”

Will Migrant Students Continue To Face Covid Racism?

Students from the Northeast have seen new waves of clinical racial bias in other parts of India. Will students from India face racial prejudice overseas this fall? In an altered, fearful world, what does it mean for racism against students?

Pandemics are also associated with migration and movement. Naturally, migrant populations are especially vulnerable to the violent prejudices brought about by the fear created by the pandemic. As international student movement starts to return to normal in Western nations, we face inevitable questions about the new predominant strain of the virus, the Delta variant – and its supposed country of origin, India. Happily, it is no longer called the India variant as it was called in its initial days. Global conscience, sharp after then-President Donal Trump’s loud denunciation of “the China virus” ensured that the association of countries and communities with virus strains were nulled quickly. Language shapes memory, and one hopes this delinking of location and virus has helped. But as a slowly healing world – especially the West – faces a single dominant strain, what happens to students from the part of that world who go elsewhere to study?

India has been bruised and battered by internal prejudices against communities sharpened by the fear of the virus. There are endless stories of migrant workers being singled out, ostracized, and harassed by their local community members even after they have followed mandatory quarantine periods following their return. Frontline workers such as doctors and nurses have been targeted, many of them rendered homeless following their eviction by landlords, forced to sleep in staffrooms or washrooms of hospitals. And we all know about the horrific anti-Muslim biases that were flamed after the infections that came to surface following the religious meeting by members of Tablighi Jamaat, an Islamic missionary and reformist organization, from all over the world at the Nizamuddin Markaz in Delhi in the early days of the pandemic.

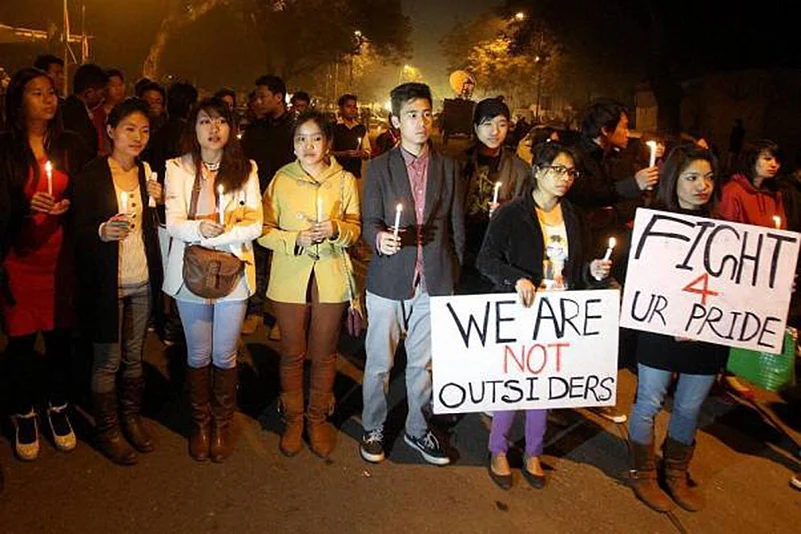

While the world fumed at what an ignorant American President called “the China virus”, what others have named “Kung Flu”, imagining horrific nightmares of biological warfare, the worst instances of Covid-racism in India have flamed against people from a regional community whose “Indianness” have long-been questioned due to certain aspects of their physical features – people from the various states of North-Eastern India. During the long Covid, clinical racism against such people have become mundane affairs in different parts of India, with them having been spat at, socially avoided, evicted by landlords, denied of employment and healthcare opportunities. As a large group of youth from the north-eastern states migrate to large cities in different parts of India to pursue their studies, racism against these students have taken particularly egregious forms. Elite institutions of higher education have reported a wide range of Covid-driven racial events, both social and institutional, enacted against these students. These include Kirorimal College at the University of Delhi, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, as well as National Council for Educational Research and Training, Delhi.

Students familiar to earlier calls of “chinki-winki” or “ching-chong” while walking the streets now hear “Corona, corona” hurled at them while they walk. Virtual spaces are as toxic as physical ones. One former Delhi University student filed a police case against someone calling her “bat eating tribe” on Twitter.

The defining feature of a pandemic is that it spreads through migration. The question is, who travels? And along what hierarchy of power? It is now clear that the Covid pandemic first came to India with the affluent, professional class who travelled internationally – not the teeming millions who slummed it out at home. Has that led to any prejudice against the middle-class and above? Have the prejudices against the participants in the Tablighi Jamaat gathering even fractionally matched the Hindu pilgrims and sadhus who gathered in the super-spreader Kumbh Mela?

We all know the answers. Racism, even when linked to pandemics, follows the balance of power. Students from India, like other international students, have had a nightmare year all through 2020 under reactionary Western governments such as that of Trumpist America who have tried to legislate every sort of affliction against vulnerable students caught in transit or in the nowhere land of online instruction.

Looking ahead, we see different realities – a sharp rise to student visas granted to the US, a more favourable government – but also the slow rise of a variant of the pandemic associated with India. What does the immediate future look for Indian students going abroad in the face of these realities? In an altered, fearful world, what does it mean for racism against students from the developing world?

(With research input by Harshita Tripathi. Saikat Majumdar writes about arts, literature, and higher education. He tweets @_saikatmajumdar. Views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect those of Outlook Magazine.)

-

Previous Story

Jammu & Kashmir Elections 2024 Dates: Voting In 3 Phases On Sept 18, 25 And Oct 1, Results On Oct 4 | Full Schedule

Jammu & Kashmir Elections 2024 Dates: Voting In 3 Phases On Sept 18, 25 And Oct 1, Results On Oct 4 | Full Schedule - Next Story