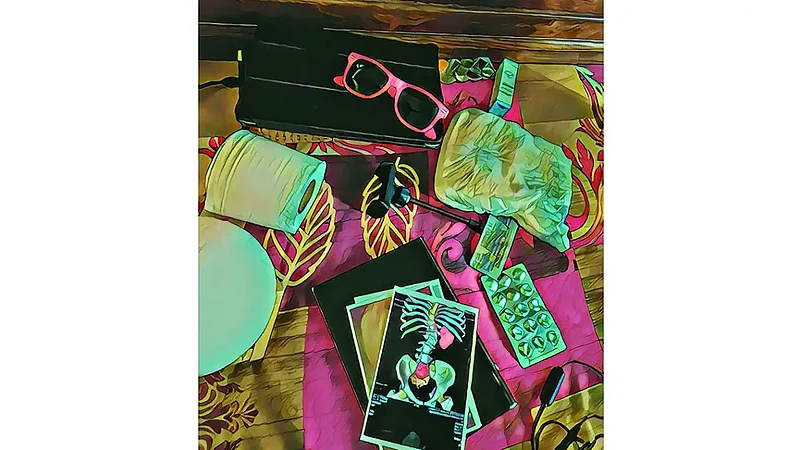

Fot two to three months every year, I am bedridden. Hours go by and I hardly move. My bed becomes an island where only essential visitors—a poetry book, some medicines and my phone—are allowed. What would you do if you were stranded on an island? I read a little, and listen to some music. My only connection to the outside world is my phone. Without the phone and a working internet connection on it, I might just drift away, taking along the island with me, deep into the sea. You lose sense of time when you are chronically ill.

On Disability And Loneliness: A Room Of Our Own

A personal account of living with an illness and bonding with the like-minded over disability, disease, queerness and poetry

Scroll up. Scroll down. Scroll up.

During these days of illness, most of my frie-nds live on my phone, on social media. Old and new friends. Distant and intimate friends. They share poetry, funny videos, and their vulnerabilities with me and I share mine. In the years of living as a person with disability and illness, the idea that you don’t have to physically meet someone to be friends with them has grown on me. If we have a connection, that’s enough.

That said, friends who make the extra effort to visit you are definitely special. Limited mobility and prolonged illness result in days when you can’t go out. On such days, they have to take the initiative. They have to understand you, and to a certain extent, your body. Friends who know why you rush to the toilet after every hour or why you have an old mug beside your bed are keepers. Friends who never doubted you for cancelling plans because of the illness are meant to be preserved. Many unsaid rules become part of friendships. Like thinking about accessibility while making plans, pity is prohibited, etc. Why is it so hard for people to feel good about themselves?

Online or offline, I require friendships that heal me. Being ill can be very isolating, and over the last few years, the pandemic has taught that to all, even the able-bodied. When you are trapped in a room for days on your own, when sensory deprivation catches up quickly, or when things that seemed alluring only yesterday are now mundane and boring. Silence that felt calming yesterday makes you uncomfortable. Anxiety takes no time to get the better of you. A trip to the bathroom can become a cumbersome activity. Even the idea of productivity seems oppressive.

After a point, you become full. Full of emotions. And the need to pour these out. Many of us navigate spaces on the internet to find a place to rest, empty ourselves out. We find that person in a stranger who might have seemed a little creepy on some other night. But today we want to believe that the world is a better place. We find that person in a crush who always seemed beyond our reach in the real world. There is no harm in trying. We find them in common friends, acquaintances, those with similar politics or taste. We are desperate to find someone, maybe because we are trying to find ourselves. Someone who gives you their undivided attention and listens to you can be a very validating experience.

“I don’t drink water when I go out in the field for work. What if there is nowhere to pee?” a woman I met at a party casually remarked while talking about working in rural Bihar. Little did she know that I too had my ‘no water’ days, having lived with chronic urinary tract infection since childhood. That conversation was the start of a beautiful friendship. We are still friends, although we no longer talk about urinary tract infections. Of all things, our shared experiences of a disease helped us form a bond that turned into friendship. If people are vulnerable and open, they allow others to be the same. This helps to establish a trust that makes others comfortable about sharing the most intimate aspects of their lives.

We all have this urge to find people who are like us. When we are lonely, we find the idea of shared nationality, region or language, therape-utic and comforting. And when we live in the margins, we look for other people who would affirm our life stories and give us some sort of hope. ‘Able-bodied people don’t get me’, I would often complain, rather unfairly since all of my closest friends are, and are beautiful human beings full of empathy. But empathy has its limitations.

When two disabled persons talk, the common strands of vulnerability help to form stronger ties. Every disabled person has their unique bodily experiences, yet the way you feel about the able-bodied gaze, the stigma, the shame, the insecurities, are often similar. I have spent hours talking to social media friends about which diaper to use, and other methods to evade any public embarrassment caused by our fragile bodies. At other times, it is about the difficulty of walking on slippery surfaces or the pros and cons of using a wheelchair vis-à-vis crutches.

When I was younger, friendships were defined by our shared nostalgia in time and space. As I grew older, my idea of friendships changed. You can hang out with people and still end up feeling bad about yourself. Friends are people who become part of your internal healing. A friendship is indifferent to age or gender. There are people who get you, alb-eit all you have are fleeting conversations to show for it. The search for solace online has made it easier for me to make friends and not expect friendships to validate every aspect of my personhood.

Other times, I have found friendships in just watching people from a distance. Watching their everyday happy and sad experiences, their journey, and their interaction with the world, living persons and inanimate objects. They resonate with me, give me solace. I have been there. I want to be there. It would be naive to expect every friendship to be a lifetime affair in a world where everything is temporary, including my body.

Friendships help me to make sense of myself, my body, my personhood. What are the things that make me worth talking to? In the last few years, I have become friends with people much older and perhaps wiser than me. I have also become friends with younger people who make me nostalgic about youth and teach me the value of being hopeful. I have connected with people over disability, disease, queerness and poetry. I have formed a bond of shared nostalgia. I have shared stories about love and heartbreak. In all these friendships, I attempt to connect with my inner self, which might sound like an immodest idea, but isn’t that a goal worth aiming for? After all, what is the use of a friendship if it doesn’t help you understand yourself and grow along this life’s journey?

(This appeared in the print edition as "A Room of Our Own")

ALSO READ: Bonds And Verses: A Circle Of Urdu Poets

(Views expressed are personal)

Abhishek Anicca is a Patna-based writer and poet, who identifies as a person with locomotor disability and chronic illness

- Previous Story

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana - Next Story