Two Muslim men were arrested in Madhya Pradesh’s Morena district in June, soon after Chief Minister Mohan Yadav declared 2024 the “Cow Protection Year”. They were charged under the MP Govansh Vadh Pratishedh Adhiniyam, 2004 for allegedly being in possession of beef, cow skin and bones in their house. An order of detention was subsequently passed by the Collector, detaining both under the National Security Act, 1980 (NSA). Within a week, both their houses were demolished, on claims that they were illegally built.

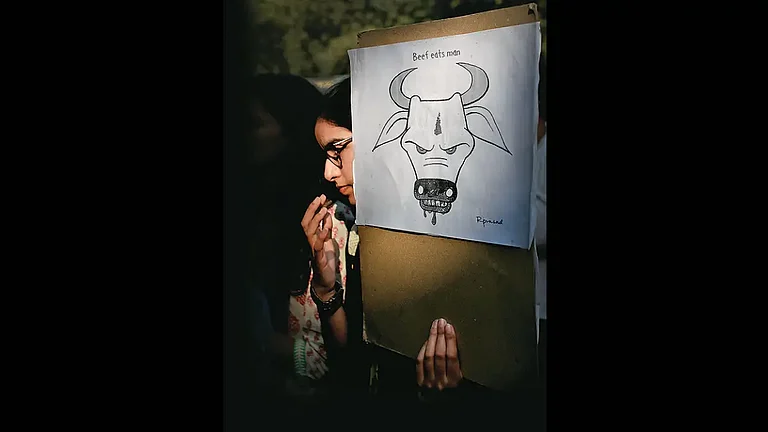

Detain And Punish: National Security Act And Cow Slaughter In Madhya Pradesh

In Madhya Pradesh, a series of cow slaughter prosecutions have taken place in the past few years. In June 2024 alone, there were three instances of detentions under the NSA, followed by the demolition of the accused’s houses

Though India is the world’s second-largest beef-exporter, there is nothing new about a ‘cow belt’ state invoking the NSA in cow slaughter cases under the pretext of ‘disturbing public order’. In Madhya Pradesh, a series of cow slaughter prosecutions have taken place in the past few years. In June 2024 alone, there were three instances of detentions under the NSA, followed by the demolition of the accused’s houses in the Ratlam, Seoni and Morena districts.

The NSA, a successor to the emergency-era Maintenance of Internal Security Act, allows preventive detention without any formal charges for up to 12 months if authorities believe a person is a threat to national security or public order. The Act derives its legitimacy from Article 22 of the Constitution, which empowers Parliament to enact laws providing for preventive detention. The NSA is therefore designed as a preventive measure, not a punitive one, making it constitutionally exempt from safeguards against detention provided in other laws. The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the NSA in AK Roy, stating that Parliament is competent to enact preventive detention laws.

As in Morena, the Seoni and Ratlam incidents reveal the pattern the State follows in invoking the NSA for cow slaughter. On perusing FIRs and newspaper reports of such cases, we found that a cow slaughter complaint is typically filed in a particular place against an identified or unidentified person. The accused, once identified by the complainant, is swiftly arrested, then designated a possible threat to public order. Upon a recommendation by the police to the district administration, an order of detention under the NSA is passed by the Collector. In all such cases, the accused's houses have been demolished by the Municipal Corporation and police upon the sudden discovery of their “illegal nature”.

We attempted to access the FIRs in similar cases registered 2021 onwards on the MP Police portal. Despite being required by law, in most cow slaughter cases where the NSA was invoked, FIRs were not made available online by police stations. However, all other FIRs registered during that period, including cow slaughter cases where the NSA was not used, were available. Newspaper reports reveal that this modus operandi — criminalising cow slaughter through detention in MP — extends as far back as 2019.

The Allahabad High Court, in Saeed vs. State of UP, observed that slaughtering a cow in private and away from the public eye in dark hours, perhaps for survival or meat consumption, cannot be used to invoke public order’ for the purpose of the NSA. However, in Morena, the NSA was invoked in near identical circumstances, where the meat was allegedly seized from the accused’s house, explicitly not a public space. The MP High Court, in Pappu Safiuddin Qureshi vs State of MP, also observed that to take preventive detention actions, authorities must have legal ‘satisfaction’ that the presence of such a person in society would be prejudicial to public order. In these instances, the accused were arrested for cow slaughter and remanded to judicial custody. Despite no apparent disturbance of public order, the NSA was invoked post-facto, curtailing the accused’s right to seek bail. Notably, offences under the cow slaughter Act are punishable by a maximum of 7 years for which arrest cannot be made by default.

These cases demonstrate how the NSA is used to curtail the liberty of the accused by circumventing the regular criminal trial process. The law, being preventive in nature, clearly suggests that it must be invoked in case of a foreseeable threat to state security or public order, not as a punitive measure by detaining an accused for up to one year based on mere accusation. While the NSA provides for detention under the Act to be subjected to scrutiny by the Advisory Board, detainees are not entitled to legal representation in making submissions before the Board.

The absence of legal representation in challenging the order of detention becomes particularly dire, given detainees’ usually marginalised socio-economic status. The detenues in these cases are predominantly working-class and oppressed-caste Muslims. Even in cases where both Muslim and non-Muslim accused were charged, such as in Seoni, initially only the Muslim accused were detained under the NSA and their houses razed. Thus, detainees’ right to life, livelihood and liberty have been constitutionally violated.

The NSA is a crucial weapon in the police’s detention armour until recently coupled with the repealed Section 151 of CrPC, which until thus far has empowered officers to detain a person whom they know has a design to commit a cognizable offence, if the officer thinks it cannot be prevented otherwise, without an order of a Magistrate or warrant. This section has also found its way in the newly formulated Bhartiya Nagrik Suraksha Sanhita. The perils of constitutionally sanctioning the formulation of preventive detention laws through Article 22 was succinctly underscored in the Constituent Assembly by Mahavir Tyagi in 1949. “In no constitution of the world have I read of such criminal law being enacted by the constitution-makers. We are here to guarantee the rights of the people and not to make criminal laws to deprive people of their rights.”. Unfortunately, Tyagi’s prescient observations continue to ring true seven decades later.

(The authors are members of the Criminal Justice and Police Accountability Project (CPA Project) based in Madhya Pradesh.)

- Previous Story

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana

Elections 2024: Ashok Tanwar Joins Congress Again; Sehwag Endorses Congress Candidate In Haryana - Next Story