Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s famous anti-corruption promise—na khuanga, na khane dunga (neither would he indulge in corruption nor would he allow anyone)—is set to face an acid test just at the time when the country’s eighteenth parliamentary election preparations are reaching the final stage.

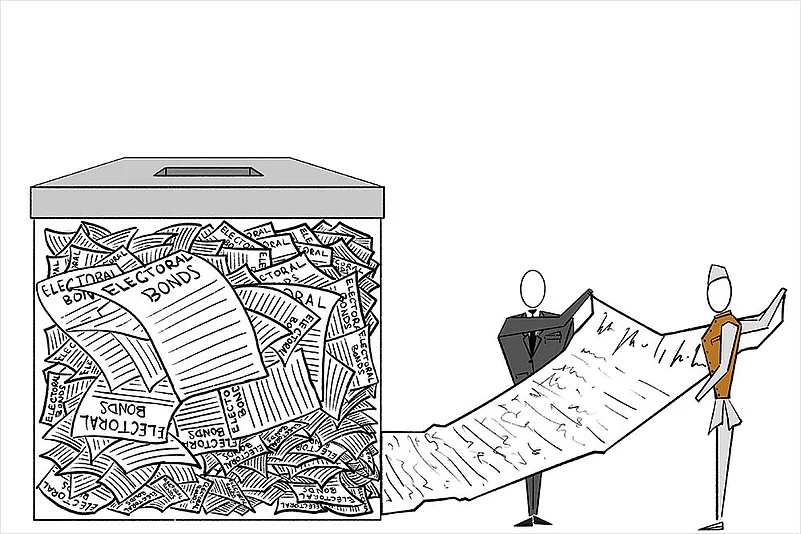

Bonding With The Bonds

The revelation of donor-recipient connections in electoral bonds may cause discomfort to the BJP—the biggest beneficiary. But many others are looking for cover, too

The election dates have been announced, parties have started naming candidates and seat-sharing adjustments between allies are being finalised. The rules of the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) have been notified, rekindling memories of the 2019 protests due to the sharp polarising ability of the legislation. Former President Ramnath Kovind-led committee has submitted its report recommending “one nation, one election” in the country—another highly controversial and polarising subject.

But it is the developments at the Supreme Court and the resultant release of hitherto secret information on anonymous political funding through electoral bonds that continue to grab public attention. Such an amount of corporate donations has never entered India’s political party system, at least not through formal channels.

The most crucial part of the data—the secret serial numbers of electoral bonds visible only under ultraviolet rays that can connect donors with the recipients of funds—is yet to be published. Even without them, it has become evident that PM Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has made massive fortunes since the introduction of the electoral bond scheme in 2018. The top court scrapped it in February, calling it unconstitutional and violative of the electors’ right to know the funders of political parties.

The scope for anonymous funding opened the floodgates for corporate ‘investments’ in political parties. From January 2018, Rs 16,518 crore was anonymously donated to different political parties over five years. The amount is equivalent to India’s annual science and technology budget and about 0.4 per cent of the Union’s total annual budget for 2023-24.

The most crucial part of the data—the secret serial numbers of electoral bonds visible only under ultraviolet rays that can connect donors with the recipients of funds—is yet to be published.

The BJP, running the Union government as well as governments in several states, secured half of it—Rs 8,251.8 crore—alone. The Congress, its chief rival, got Rs 1,952 crore—not even one-fourth of what the BJP got.

However, several regional parties got quite a massive amount of funding—West Bengal’s ruling party, Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress (TMC), got Rs 1,705 crore. K Chandrasekhara Rao’s Bharat Rashtra Samithi (BRS), which ran the mid-sized state of Telangana for nine years, encashed electoral bonds worth Rs 1,408 crore. Another mid-sized state Odisha’s ruling party, Naveen Patnaik’s Biju Janata Dal (BJD), got electoral bonds worth Rs 1,020.5 crore. Telangana and Odisha are mining-rich states, while West Bengal, too, has a sizable mining industry.

Among large states’ ruling parties, Tamil Nadu’s Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) got Rs 677 crore, while Andhra Pradesh’s YSR Congress Party encashed bonds worth Rs 504 crore.

Since the publication of the donation details, even though it is yet to be known who funded which party, people have started pointing out how over a dozen companies that came under investigation by central agencies like the Directorate of Enforcement (ED) and the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) contributed large amounts.

Rahul Gandhi of India’s main opposition party, the Congress, called the electoral bond scheme “the biggest extortion racket in the world” and alleged that funds for splitting rival political parties and toppling opposition governments came to the BJP through electoral bonds.

The Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), which rules Delhi and Punjab and is allying with the Congress in Delhi, Haryana and Gujarat, is a minor beneficiary of the scheme and has taken up the issue to target the BJP for corruption. Party leader Gopal Rai said that the BJP’s Lok Sabha election tally would not even cross 40—contrary to the saffron party’s target of bagging 370 of 543 Lok Sabha seats—once the entire data is made public.

The CPI (M), which rules the southern state of Kerala and is one of the petitioners in the Supreme Court against the electoral bond scheme, highlighted through social media platforms how lawyers representing government institutions “were trying to shield the identities of donors who purchased Electoral Bonds!”

“The BJP’s allegiance lies with its cronies! They don’t want the data to come out, perhaps because they have too many skeletons in their closet,” the party said in a social media post. The CPI (M) in West Bengal is trying hard to recover votes that it lost to the BJP over the past six years and is using its role behind the scrapping of the scheme to win over the electorate.

While the nation waits for the invisible serial numbers, it can be anticipated that the revelation of donor-recipient connections may not cause discomfort to the BJP alone.

The BJP, on the other hand, has been visibly pushed on the back foot on this issue, as its top leaders continue to try to defend the party’s position of keeping donor details secret to protect political funders’ privacy and ensure they did not face any vindictive response from rival parties. Most leaders have remained tight-lipped.

“I feel that instead of completely scrapping the electoral bonds, it should have been improved,” Union Home Minister Amit Shah said in mid-March, in his first response to one of the most remarkable defeats of the Modi government in India’s apex court.

He was trying to downplay the possible political fallout, arguing that since the BJP alone had more parliamentarians than all opposition parties put together, it is only natural that the party’s share of funds would be higher. Besides, all other parties had benefited from the scheme, Shah said.

However, the figures that have now come before the public make amply clear that the BJP has been the overwhelming favourite of companies.

The funders include a range of companies—from mining, power, telecommunication, and construction to lottery, pharmaceuticals, and fast-moving consumer goods. Big corporate names like Vedanta, Essel, RP Sanjiv Goenka group and Aditya Birla group feature in this. Bigger names like Gautam Adani’s Adani group and Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance group—whom opposition parties have frequently referred to as the biggest beneficiaries of the Modi rule—are not directly present on the list.

However, Qwik Supply Chain purchased bonds worth Rs 409 crore. Its whole-time director, Tapas Mitra, also holds directorships of over half a dozen Reliance group companies.

Besides, some little-known companies have spent enormous sums compared to their financial strength. For example, the Kolkata-based MKJ group spent over Rs 600 crore.

The huge sums donated by some of these companies have raised the obvious question—was there a quid pro quo? Did these funds change government policies? Were some of the big companies funding through shell companies?

In the Supreme Court, the State Bank of India (SBI), which is controlled by the finance ministry, fought hard to ensure that the connection between donor and recipient does not become public knowledge. It has failed so far though its lack of interest in complying with the top court order was made so obvious that still more twists in the tale cannot not be ruled out.

Meanwhile, the opening of statements of various parties submitted before the Supreme Court in sealed covers has already revealed some connections. Parties like the AAP, Tamil Nadu’s All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) and the DMK, Maharashtra’s Nationalist Congress Party (NCP), Karnataka’s Janata Dal (Secular) and Sikkim Krantikari Morcha (SKM) have voluntarily disclosed who they received the bonds from. Except for the DMK, all others are minor beneficiaries of the scheme.

When it was first revealed that the biggest political donor was Chennai-based ‘lottery king’ Santiago Martin’s Future Gaming and Lottery Services—with a whopping Rs 1,368 crore, or over 8 per cent of the total funding through bonds—many social media users and political activists expressed their suspicion that the BJP was the biggest beneficiary. They highlighted how the company faced probes from central agencies. Critics highlighted how Megha Engineering, the second-highest donor, got rewarded with projects by the state BJP governments.

However, the DMK’s voluntary declarations reveal that the party—a crucial component of the INDIA opposition bloc—received Rs 509 crore from Martin’s company and Rs 105 crore from Megha Engineering. These two companies have turned out to be the DMK’s prime funders. The revelations mean that the biggest donor gave 37.4 per cent of its total political funding to an opposition party.

The majority of the bond recipients, however, have not disclosed donor details. As the scheme does not require parties to keep details of funds received through the bonds, several parties informed the apex court they did not maintain any records. The TMC and Bihar’s Janata Dal (United) have told the top court that they have no idea whom they received their donations from.

The JD (U)’s response, perhaps, exemplifies what the scheme of anonymous funding was meant for. They wrote: “Somebody came to our office on 03-04-19 at Patna and handed over a sealed envelope and when it was opened we found a bunch containing 10 Electoral Bonds of Rupees One Crore each.” The TMC’s response was similar.

While the nation waits for the much-sought-after, invisible serial numbers, it can be anticipated that the revelation of donor-recipient connections may not cause discomfort to the BJP alone.

- Previous Story

Marital Rape 'A Social Issue Not Legal', Centre Files Affidavit With SC Against Criminalisation

Marital Rape 'A Social Issue Not Legal', Centre Files Affidavit With SC Against Criminalisation - Next Story