Saraswathi D. is an activist, a writer, an academic, a performer, storyteller, and a translator. She has spent the last several months translating what is perhaps India’s most important text on the history of Dalit women’s activism, We Also Made History: Women in the Ambedkarite Movement in Maharashtra by Urmila Pawar and Meenakshi Moon.

The Business Of Translations: How Badly Translators Are Paid And The Minimal Attention They Get

For years, Indian publishers have sought government help that will allow them to pay translators a decent wage for their work so that literature can speak beyond the borders

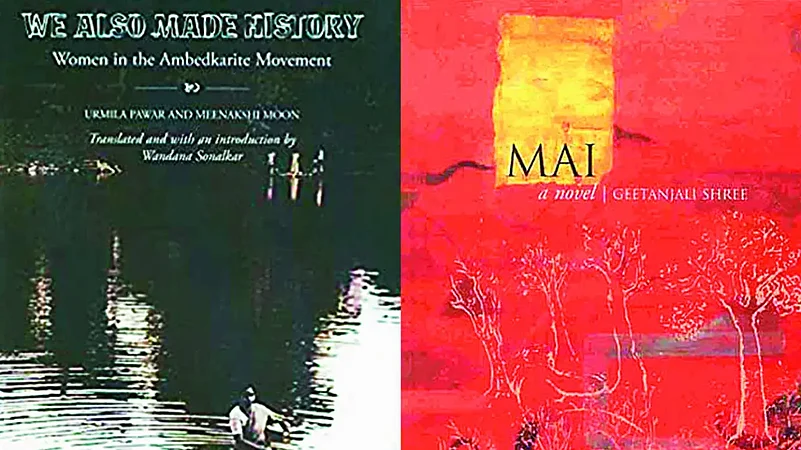

Written originally in Marathi, the book was translated into English by Wandana Sonalkar of Aalochana, a women’s group based in Pune. Saraswathi does not read Marathi, and is only working from the English, something that would give translation purists a mild heart attack. But for Saraswathi, there is a singular motivation: this book is too important, and needs to be available in different languages now. If the only way to do it is via another language, so be it. She talks about the work that goes into doing a translation: researching the subject, contacting the authors if available, checking out the pronunciation of words so as to render them as they are meant to be heard and read, and so much more. She does all this because for her, translation is a deeply political act.

For Deborah Smith, celebrated translator and the UK publisher of Geetanjali Shree’s Booker award winning novel Tomb of Sand, translation is an equally important, and yet somewhat different kind of commitment to literature and writing. She speaks of it as something that purveyors of literature, i.e. publishers, can do, and should do. In many ways, she points out literary translations—by opening up what are relatively ‘unknown’ worlds (or worlds often known only in terms of their stereotypes) in all their complexity—break down national boundaries and show how literature can speak beyond these borders.

And yet, translations are not easy to do. Nearly 40 years ago, when we began Kali, and later, after Kali’s closure in 2003, when we set up Zubaan, we were clear that translations from Indian languages into English would be central to our publishing. But the initial questions that arose were: how do you know what to translate? Where is the information that will allow you, as the publisher, to begin the process of knowing other literature in order to choose from there what you want to publish?

The answer is, there isn’t one. In countries where translation into and from different languages is part of the literary universe, certain signposts help publishers to look at possible books—catalogues, sample chapters, information about the author, and so on. In India, this kind of support for literature is virtually absent. And the inevitable fallback then is picking up books recommended by people you know about people they know. Alongside the unavailability of information about books, there is paucity of information about translators. Even if you were to find something you really wanted to do, where and how would you find a translator? In a recent negotiation over a Japanese translation of one of our books, the translation agency in Japan (and yes, there was an agency!) informed us that they put some part of the content of the book out into the world for possible translators to work on (almost like a competition), and then they chose the best from the many applications they received. Something like this would be unthinkable in India today.

The impossibility has to do with that old cliché about how badly translators are paid, and the minimal attention the translator is given—almost as if they were not skilled and creative people, but just a service to writers.

As feminist publishers, translation has always been integral to our practice, and of the first few books with which we began Kali in 1984, one was a novel, MK Indira’s Phaniyamma, translated from Kannada, and a volume of short stories, Truth Tales, which included writings from Bengali, Hindi, Oriya, Tamil, Malayalam, Gujarati and Urdu. The book had some firsts: the first English translation of an adult story by Mahashweta Devi (previously only a children’s story had been translated into English)—and perhaps the second time Ismat Chughtai had appeared in English (one of her stories had previously appeared in Indian Literature published by the Sahitya Akademi).

This too is another little-known aspect of translation—often the risk of finding new voices is taken by smaller, independent publishers and, in the fitness of things, authors (and this happens regardless of whether the book is translated or not) move on to publishers who can give them wider exposure and more money.

This is not necessarily a bad thing. Smaller publishers have more independence in decision-making. Their decisions are not always tied to profit. Some 20 years ago, we were proud to publish the first English translation of Geetanjali Shree’s marvellous fiction novel, Mai (which was what led the publisher of Tilted Axis in the UK to mark her as someone to be translated into English). The fact that today she and her translator, Daisy Rockwell, take their rightful place in the world of literature internationally, is a cause for us to celebrate.

While translation struggles with all these issues, it also survives and thrives. In recent years, more and more publishers in India have begun to look at translation between Indian languages. Money for such enterprises is still scarce, but an increasing number of translators, in particular young people who are bilingual, are showing an interest. While we began publishing translations from Indian languages virtually the moment we began our publishing, one of the things we were unable to do, until recently, was to look at the reverse—the process of taking feminist literature published originally in English into Indian languages. Last year, by a stroke of luck, this changed. In partnership with the Prabha Khaitan Foundation, we put in place a programme of translating feminist literature published by Zubaan in Indian languages. The Foundation’s support allows us to pay translators a reasonable amount for their work, and to support publishers with some small editorial costs.

Our initial uncertainty about whether there would be an interest in feminist books among Indian language publishers—they are not huge money-spinners—soon turned into delight as we found more and more publishers and translators coming forward. It’s been six months into this collaboration, and we already have 18 books being translated into as many as eight languages.

For years, Indian publishers have said that for translations to thrive there need to be subsidies that allow us to pay translators a decent wage for their work. Across the world there are examples of translation programmes—from Japan, Poland, Hungary, Romania, Turkey, France, Germany, and more—that allow their literature to travel. At international book fairs, these translation subsidies—often offered by the State as a way of promoting their literatures—are widely available and have many takers. Geetanjali Shree’s award has shown it is possible. Now it’s up to us.

(This appeared in the print edition as "The Business of Translations")

(Views expressed are personal)

Urvashi Butalia is the founder of Zubaan Books