On October 31, Ashok Swain, an Indian-origin professor of peace and conflict at Uppsala University in Sweden, wrote in a tweet, “India is like the Middle East & North Africa—consti-tu-tionally secular but more religious than Islamic countries, Pakistan & Bangladesh.” He then gave a list of most-religious countries, which placed India alongside Saudi Arabia, Israel, Iran, UAE, Egypt, Qatar, Turkey, Jordan and Morocco.

What Does Secularism Mean Around The World?

Secularism, in modern terms, means mostly the separation between religion and state, but it has been interpreted differently across the world

Swain has been regularly criticising the rise of religious intolerance in India and the ‘Hinduisation’ of the Indian polity. This equating of India with Islamic countries dominated by Sharia laws was alternately supported, contested and excoriated by the twitterati, some calling it thought-provoking, others rubbishing it as ‘oversimplification’.

We live in a time when the world is supposed to be a single global village. There have been attempts to design certain universal norms that apply to every place, on issues ranging from human rights and environment protection to treatment of prisoners of war. Conversely, there have been arguments against applying the ‘one size fits all’ concept indiscriminately.

ALSO READ: The Rising Tide Of The Right Worldwide

Whether or not ‘modernity’ should interfere with the lives and social systems of indigenous people which they have designed based on their own, ages-old knowledge systems, is one such question frequently raised. Why should only ideas that originated in the West be considered modern has been asked. Similarly, whether all countries or regions should adopt the same governing principles has been debated.

The idea of secularism has been one such bone of contention, in India and globally, in the world of politics and in the arena of academia. The word secular, in its modern meaning, mostly means the separation between religion and state. However, it has historically been understood in different ways, reflecting various essences, including in India.

Secularism continues to be suspected and debated. Whether the first reference to the separation between governance and religion is to be found in the New Testament, wherein Jesus famously said, “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s” is on strand of debate. Nevertheless, in pre-Enlightenment societies in Europe, it was mainly religious laws that governed societies and the administration. Questioning religious beliefs, especially from a scientific point of view, put many lives in peril.

ALSO READ: Power Politics: History Of Indian Secularism

There was no clear distinction between laws governing a person’s spiritual life and a society’s material life and there were also instances of kings proclaiming to be God, or His incarnation, or agent, or claiming divine rights to rule. Churches, too, enjoyed significant authority over public life. There were, therefore, phases of conflict between religious authorities and rulers, with one trying to establish supremacy over the other.

The first definitive reference to a separation of the two domains of state and religion comes in English philosopher John Locke’s 1689 work A Letter Concerning Toleration. He wrote, “...the Church itself is a thing absolutely separate and distinct from the Commonwealth. The boundaries of both are fixed and immovable.”

However, it took another century for the first practical implementation of the idea. It was the First Amendment of the US constitution in 1791 that said, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” While acknowledging the freedom to religious practices, the first amendment clause, according to the third US president Thomas Jefferson’s 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptists, built a “wall of separation between the church and state.”

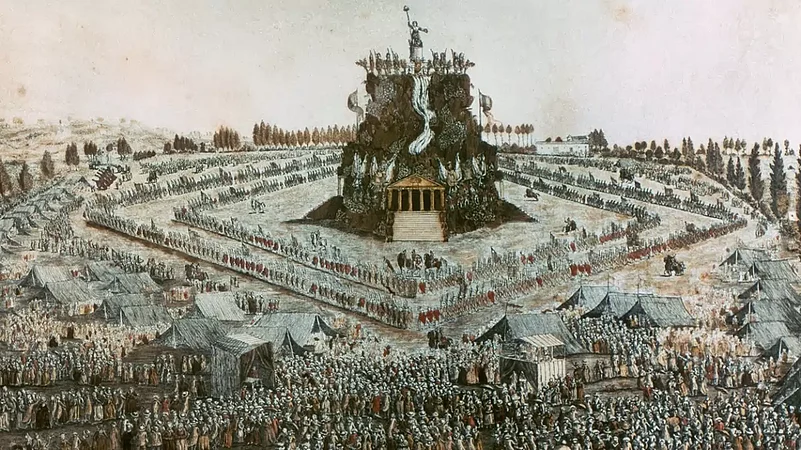

A similar move was taken in France four years after the US when, in a decree on February 21, 1795, the Constitution separated church from the state, while also acknowledging freedom of worship. It was in the middle of the French Revolution (1789-1799), following a prolonged battle to diminish the importance of church. After many phases of progress and regress in this regard, the principle was finally formalised in 1905.

The trend entered the East and the Muslim world in 1918, with the establishment of a democratic republic in Azerbaijan, the first secular government in Asia. In 1928, state secularism made major progress when Turkey, once the seat of the Islamic Caliphate, abolished Islam’s position as state religion and emerged as a purely secular nation.

Another model, a more extreme one, emerged soon after the Bolshevik revolution in Russia in 1917 and the establishment of the Soviet Union—followed by a series of communist governments being established in eastern Europe, central Asia and Latin America, especially in the aftermath of World War II. Here, the state-sponsored atheism engaged in a direct confrontation with religion. Even though Albania was the first state to be officially declared atheist in 1967, communist-led governments had pursued anti-religious policies for about five decades already.

In one sense, the rise of nationalism and communism during the 19th and 20th centuries led to the rise of secular nation states.

One word, different models

Most political theorists, however, would not include state-mandated atheism in the discussion on secularism. It is considered the middle path, between a country having a state religion and one with anti-religious policies. Charles Taylor, author of the 2007 book A Secular Age that won many accolades worldwide, wrote an essay in 2009, titled ‘The Polysemy of the Secular’, and claimed that Locke himself was as much against the Catholics as against the atheists.

According to Taylor, the meaning of the word secular changed with time and place. In the early days of its usage, certain times, places, persons and institutions were seen as closely related to the sacred or higher time, and others as out there in profane time, with the latter being called secular. For example, ‘ordinary’ parish priests were called secular against the ‘regular priests’ living in monastic institutions.

Later, the meaning of the word changed with the emergence of the concept of having a good social/political order unconnected to traditional ethics, a ‘this-worldly’ society of mutual benefit unconnected with virtue in the traditional sense.

“The attempts of eighteenth-century ‘enlightened’ rulers, such as Frederick the Great and Joseph II, to ‘rationalise’ religious institutions, in effect treating the church as a department of the state, belong to the earlier phase—as does, in a quite different fashion, the founding of the American republic with its separation of church and state. But the first, unambiguous assertion of this self-sufficiency of the secular came with the radical phases of the French Revolution,” Taylor wrote.

According to him, secularism seeks at least three ‘goods’, which can be classified in three categories of the French revolutionary trinity—liberty, equality and fraternity: people must have the liberty to choose a religious belief, or not to choose any; there must be equality between people of different faiths and no religious outlook can enjoy a privileged status; and all spiritual families must be heard and included in the process of determining what society is about.

The author-philosopher, however, cautioned against using the western frame to evaluate or judge non-western societies everywhere. “If the canonical background for a satisfactory secularist regime is a three-stage history—distinction of church/state, the separation of church/state, then sidelining of religion from state and public life—then obviously Islamic societies can never make it,” he wrote.

His comments may trigger one’s interest in the study of secularism in the Muslim-majority, central Asian countries of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. These regions, where Islam once dominated public life, came under the sway of state-sponsored atheism under communist rule and became secular—allowing religious freedom—after the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

On the other hand, in 1945, independent Indonesia was founded with Pancasila, or the five Chinese political principles, as the basis of the state. It was not officially called secular but the Constitution made no mention of Islam. The attempt was to strike a balance between the Islamists, secular nationalists, communists and the Christian minority. It was more about co-existence.

Even the western model has its differences. The French model of secularism, once globally hailed by secularists, has come under criticism in recent years for taking an anti-religion stance, particularly with regard to Islam, especially since a 2004 law prohibited wearing “ostensibly religious symbols,” including the hijab, in public schools.

A 2021 paper published by The Consilience Project, titled ‘U.S. Religious Freedom, French Secularism: Vive la Différence’ argued that “secularism in the United States is best thought of as freedom of religion, (while) la?cité is best thought of as freedom from religion. Nonetheless, both approaches keep religion out of policy-making while allowing people to worship however they wish, or not at all.” La?cité is the usual French term for secularism, even though it has been argued that it tends to imply scepticism or hostility towards religion more than neutrality.

The Indian Prism

Similarly, many Indian political theorists have cautioned against looking into Indian or South Asian secularism through the western prism. In an article titled ‘Reimagining Secularism’, published in 2013, a year before the Hindu nationalist party, the BJP, rode to power and Narendra Modi became prime minister, political scientist Rajeev Bhargava stressed the need “to move away from the standard church-state models of secularism and begin to focus instead on secularism as a response to deep religious diversity”.

Bhargava, who calls himself ‘a spirited defender of Indian secularism’, argued that secularism is not against religion but it only opposes institutionalised religious domination. “A secular state shows critical respect to all religious and philosophical worldviews, (which is) possible only when it adopts a policy of principled distance towards all of them,” he opined.

Political theorist Ashis Nandy has looked at the word from the Indian perspective quite thoroughly and concluded that formal, western-style secularisation “has shown an incapacity to keep pace with politicisation in this part of the world, and it shows no sign of being able to do so in the future.” He has repeatedly argued that the examples of emperors Ashoka and Akbar, scholar Dara Shikoh (Aurangzeb’s brother) and spiritual leaders like Kabir and the Bhakti poets, who were deeply religious but promoted tolerance and plurality, would serve as more acceptable models to Indians than the formal secular model of being publicly non-religious.

In his 1995 essay titled ‘An Anti-secularist Manifesto’, Nandy elaborated upon the contradictions of different meanings of secularism in the Indian context through the example of Mohandas Gandhi. India’s ‘father of the nation’ called himself ‘secular’ but thought poorly of those who wanted to separate religion from politics, Nandy noted, adding that Gandhi said those who wanted to separate the two understood neither.

“This contradiction has its roots in the two meanings of secularism currently in contemporary India,” Nandy wrote, adding that the first meaning says religious tolerance could come only from devaluation of religion in public and from the freeing of politics from religion, while the second meaning does not consider secularism as opposite to the word sacred, but as ethnocentrism, xenophobia and fanaticism.

“One could be a good secularist by being equally disrespectful towards all religions or by being equally respectful towards them. And true secularism, the second meaning insists, must opt for respect. It is this non-modern meaning of secularism which the anti-colonial Indian elite stressed, given the need for mass mobilisation in a deeply religious society on the basis of a broad social consensus against British rule,” Nandy wrote.

It is worth remembering that during the last two decades of India’s struggle for Independence, especially since the 1930s, religion took a dominant position in political discourse. On the one hand, Gandhi tried to unite the nation using both Hindu and Muslim religious issues, while the Hindu Mahasabha and the Muslim League tried to use religion to serve their own communal agenda. Subhas Bose, on the other hand, wanted to purge religion from the political arena altogether to unite the country.

Nandy argued that formal secularism implies that in open societies, some citizens may choose their leaders on religious grounds, or the leaders may exploit this weakness of the citizens, but both sides—the leaders and the led—“should be embarrassed about this state of affairs and know the limits of their game”.

A quarter century later, and after eight years of BJP rule, there have been demands for abolishing separate religious codes in private life by implementing a uniform civil code (UCC). The demand for deleting the word ‘secular’ from the Preamble to the Constitution—inserted in 1976—is also being raised.

Irony or not, Hindu nationalists batting for UCC often cite France’s instance of banning the hijab to bolster their argument for a similar move in India, without considering that France would, in all likelihood, also treat wearing the tilak, the Hindu sacred mark on the forehead, as an “ostensibly religious symbol”, forget allowing Saraswati puja in schools or the performance of religious rituals by Hindu priests before the launch of a spaceship or a submarine.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Around the World with Secularism")

- Previous Story

Marburg Virus Outbreak In Rwanda Leaves 11 Dead | All About The Deadly Ebola-Like Virus

Marburg Virus Outbreak In Rwanda Leaves 11 Dead | All About The Deadly Ebola-Like Virus - Next Story