In the past month, journalists from media powerhouses like the BBC, The Washington Post, Reuters, and the LA Times have raised their voices against the “dehumanising rhetoric” used in media against Palestinians and the bias in reporting of the ongoing Israel-Palestine war. One characteristic that has defined the approach of many western media outlets covering the war has been a com-plete lack of context. Most do not men-tion the sustained Israeli occupa-tion of Palestinian lands, Israel’s viola-tion of multiple international laws, and the everyday violence and subjugation of Palestinian people that have been ongoing for the past 70 years. This points to a lar-ger question of bias in media represen-tations and its inextricable connection with the politics of language.

Israel-Palestine War: Lopsided Language In Media Coverage

Coverage of the Israel-Palestine war raises the larger question of bias in media represen-tations

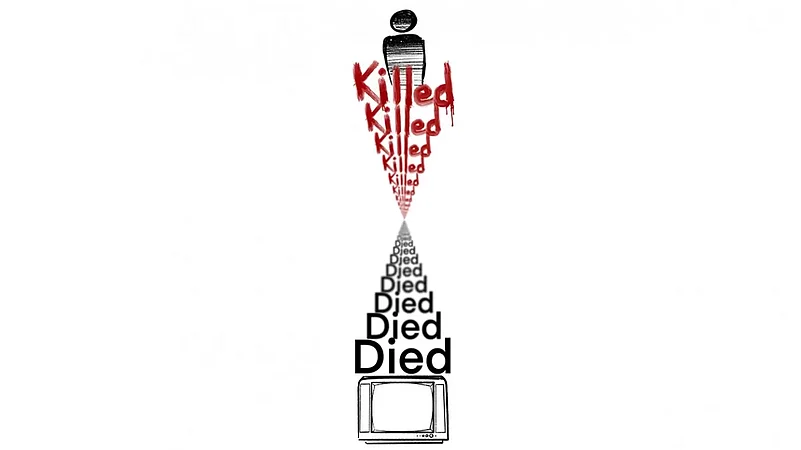

Linguistic bias is an often-ignored way in which such biases become evident. It refers to the asymmetrical use of words or phrases to describe one community in a way that reveals conscious or uncons-cious prejudice. For instance, across multiple media outlets, words like “atro-city”, “brutal murder” or “massa-cre” are reserved for referring to Israeli deaths—an observation that a study of BBC articles affirmed back in 2011. Israeli victims are described as “brutally killed by Hamas” whereas Palestinian victims “die” as “collateral damage” in “zones of conflict”. Headlines refer to buildings “collapsing” in Gaza without any men-tion of the Israeli airstrikes that have destroyed them. Such euphemisms misrepresent the state of the war and hide the extent of damage that Israel has caused in Gaza.

The New York Times recently changed the title of an article thrice to whitewash Israeli involvement, going from calling the attack on a hospital an “Israeli attack” to describing it as an “explosion” at a hospital in Gaza. Holly Jackson published a study in 2021 highlighting how NYT reporting during the first and second intifadas (1987-1993 and 2000-2005) showed a clear anti-Palestinian bias through criteria such as the use of active or passive voice and that of violent language. Her ongoing work shows that NYT’s mention of Israeli deaths increased as more Palestinians died in the first 10 days since October 7. The work also reveals that words like “slaughter”, used 53 times in this time period, are always in reference to Israeli deaths and never to Palestinian deaths. Her data also suggests that it takes 17 Palestinian deaths as opposed to three Israeli deaths for it to be mentioned in the Wall Street Journal. In cases where Palestinians are described as ‘‘killed’’, Israel is rarely identified as the perpetrator of the violence or even mentioned in conjunction in a way that could create an association.

This phenomenon is not isolated to the West and a continuity of this discourse can be observed in Indian media as well. For instance, India Today’s report on November 20 describes Hamas as a militant group which went on a “rampage into Israel” and killed 1200 people. They go on to say that “authorities in the Hamas-ruled Gaza Strip said that 12,300 have died so far.” Here, only Hamas has gone on a rampage and taken hostages. By describing the Gaza Strip as ruled by Hamas, it insinuates doubt on the credibility of the data. Further, while the 1200 are ‘‘people’’, the 12,300 are not referred to as people but as numbers who have “died”, not “killed” by targeted missiles. It is also notable that while many Indian media houses have flown journalists into Israel, they have often refused to extend the same courtesy done in the name of good journalism to spaces of conflict within the country such as Manipur.

The lopsided emphasis on Israel is? also visible in the reportage of hostage releases. Western media has tended to name Israeli hostages, talk to their families, and share personal stories while Palestinian prisoners remain completely invisible. In the release of the first group of hostages, the 17 Israeli hostages received disproportionate attention and made the headlines while many reports did not even mention the Palestinian prisoners. When mentioned, they were often unnamed and the fact that they include 22 women and 17 minors, 15 boys and two girls, finds no relevance. There is also an absence of any reference to Israel’s draconian prison industry which holds more than 10,000 Palestinians, with 500-700 Palestinian children as young as 12 arrested per year on charges such as stone-throwing.

All of these linguistic and representational biases reinforce antagonistic attitudes towards Palestinians and demean their value of life. In his book, Less than Human, David Livingstone Smith argues that dehumanisation leads people to see a particular community as sub-human, which makes them unworthy of life and dignity. This thinking opens doors for genocide and mass murder.

Rhetoric such as “human animals”, “children of darkness” and “monsters in Gaza” used to describe Palestinians by members of the Israeli government are all instances of dehumanisation. This is also the logic behind Prime Minister Netanyahu reference to ‘‘Amalek’’—an enemy of Biblical Israel—to justify gen-ocide. When leaders use such language, it is no surprise that followers on social media call Palestinians “cockroaches” or “vermin”. Israel’s American allies have also called the Hamas attack Israel’s 9/11 with Joe Biden going so far as to say that it is like “fifteen 9/11s”. Such rhetoric thrives in association with orientalist attitudes, which according to Edward Said refers to ideas about western supremacy and stereotypical perceptions of the Middle East that are manifest through “representations, rhetoric, and images”. It consistently paints the oppressor as a victim who has no choice but to retaliate while completely ignoring the decades of violence perpetrated by the oppressor that has led to this moment.

The vilification of a group of people normalises a sense that they don’t des-erve human rights and serves to justify the infliction of horrific violence on them. This is nothing new. In fact, oppressors have consciously manipulated language to legitimise genocides throughout history. It is well-known that the British colonial enterprise saw Indians as uncivilised barbarians who were the “white man’s burden”. Native Americans were described as “merciless savages” and “soulless animals” who had to be killed for the coloniser to possess the “promised land” of America. From the 1994 Rwandan genocide to the South African apartheid systems, the politics of language has powerfully shaped conversations about who deserves to live, have access to resources, and to human rights. Nazis referred to Jews as “rats” and “parasites”, legitimising their mass murders. American propaganda during WWII called the Japanese “yellow vermin” and described them as “beasts” who only understood the language of violence as they dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Advertisement

Dehumanising language has accompanied massacres, slavery, and all histories of oppression, and it continues in the ongoing genocide of Palestinians. Through consistent use of such rheto-ric in the media, people become the metaphors and names used to describe them—vermin who must be exterminated so they don’t cause a plague or sub-humans whose deaths need not be counted. Words shape perceptions, and perceptions assign value to life and dignity. The ongoing war and the politics of language surrounding it prove this yet again. History serves as a dire warning of where the use of such language, if left unchecked, will lead.

Advertisement

(Views expressed are personal)

Shobha Elizabeth John is a senior research fellow at the indian institute of science education and research

(This appeared in the print as 'Lopsided Language')

-

Previous Story

After Kursk, Ukraine Claims To Have Taken 'Full Control' Of Russian Town Sudzha

After Kursk, Ukraine Claims To Have Taken 'Full Control' Of Russian Town Sudzha - Next Story