Did you ever call any woman a crone? Did you ever get called one? The slur associates, as though naturally, the disagreeable with the ageing female body. Crone etymologically relates to the French word for carcass. But the earliest known usage of the noun crone, in the sense of the withered hag, dates only to the Middle English Period beginning from the 13th century or so. This conjunction of the decaying female body and disparagement appears then to be the mark of a certain order of history.

In Indian Mythology, Goddesses Show That 'Old' Women Are Powerful

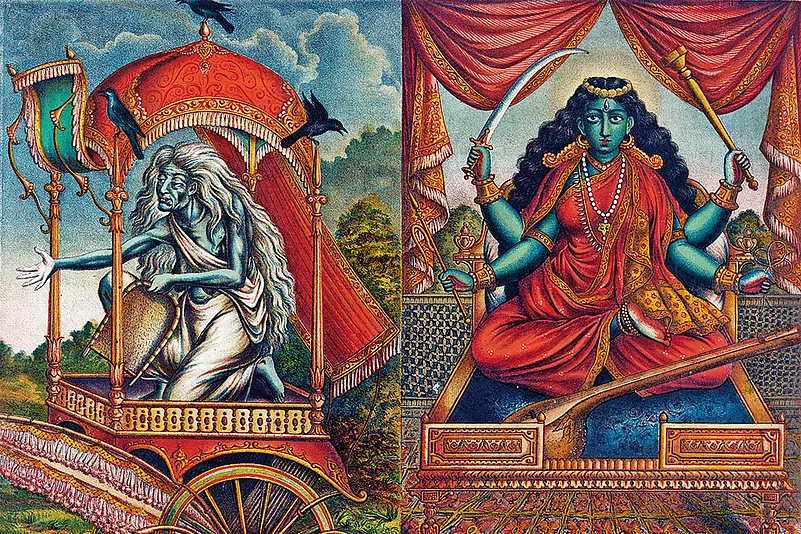

Despite gaunt bodies, sagging breasts and stomachs, goddesses present us with powerful images of old women

In the earliest religious layers of most cultures, the old and the young female selves were mythically understood as the anthropomorphic features of the earth. It was a recognition of the Earth Mother as the source of life who embraces growth and decay; receives corpses and sprouts crops. She symbolised the organic cycle of life. The old mother and the young maiden represented a symbiotic relationship rather than one of derision and desire.

The fragmentation occurred perhaps with the steady rise of the ‘P’ world: plough, primacy of paters, patriarchy, private property and phallic symbolism. An attendant corollary was both sexualisation and demonisation of the earlier assumptions of the powerful feminine. The productive female was recognised and put on a domesticated pedestal, while those outside the reproductive cycle, often the chthonic goddesses, were reviled. In the overwhelming function of legitimate reproduction, the chaste womb was of the essence. No wonder the laws of Manu lay down that, “A thirty-year old man should marry a twelve-year-old girl … and a man of twenty-four an eight-year-old girl…Women were created to bear children” (9. 94 & 96). Female age became an essential matter: “Her father guards her in childhood, her husband … in youth and her sons … in old age…A woman is not fit for independence” (9.3). And that was happiness for “where the women of the family are miserable, the family is soon destroyed” (3.57).

Yet it endures. A vital force of life beyond the womb. Age does not wither their agency. They remain as Mother Earth, Corn Mother, Warrior goddess, Protectors of cattle, children, forts, fertility, health, happiness, destroyer of evil… And they are often venerated as ‘Burhi’—the old— particularly in the laukika or folk forms of Hinduism.

***

Jyestha.

The goddess has faded from popular memory. The term means the elder, which is a relative identity. The moot point is, older than whom?

In the earliest religious layers of most cultures, the old & young female selves were mythically understood as the anthropomorphic features of the earth.

In the Baudhayana Grhyasutra, Alakshmi is significantly referred to as Jyestha. In the Padma-purana, Alakshmi rises from the churning of the milky-ocean before the appearance of Lakshmi:

Then Alaks.mī, of a dark face and red eyes, having rough and tawny hair, and having an old body, sprang up. She, the eldest one… The gods spoke…: “O goddess… Always remain, causing misery, in the houses … bereft of sacrifices (offered to) preceptors and gods…and where the sound of the Vedas is absent.(4. 9. 7-22)

The samudra-manthan continues and,

… on the twelfth day in the morning … the great Lakshmi, graced with all (auspicious) characteristics, sprang up. All the religious deities saw that great mother of all creatures having her abode in the heart of Vishnu, and were delighted. (4.10. 1-4)

Jyestha-Alakshmi is “the eldest one” who is not associated with the Vedas or the yagnyas. Unlike Lakshmi, she knows no conjugal felicity. Her description as dark, old and ugly symbolises her decrepit moral provenance from the perspective of the composers of the purana. Alakshmi in parts of Bengal is fashioned out of mud, cow dung, water, and fanned with a winnowing tray. Often, she is ritually evicted before the worship of Lakshmi can commence. Does not the fashioning suggest an agrarian mother-goddess?

Significantly, the epithets and associations Lakshmi (and Sri) in the Sri Sukta that belongs to the Khila Sukta section appended to the R.gveda, suggest deities of fertility and vegetation too. Sri is mentioned as living in karisini/cow dung and kardama/mud is her offspring (mantras 9 & 11). Lakshmi is hiran.mayīm./golden and pingalam./golden-yellow (mantras 1 & 14); colours which are associated with the ripe corn in harvest festivals. But she is no wife. Not yet. Mantra 8 of this sukta mentions Jyestha-Alakshmi and associates her with hunger and thirst. Is it a coincidence that the hymns of the Devi Mahatmyam also salute the goddess as both hunger and thirst:

Ya devi sarvabhutesu kshudarupena samasthita…

Ya devi sarvabhutesu trishnarupena samasthita…

Namastasayi, namastasayi, namastasayi, namoh namah.

(5. 26-28 & 35-37)

P V Kane’s A History of Dharmashastra (1957) mentions a Jyesthavrata where Jyestha is “identified with Lakshmi and Uma” for removal of Alakshmi (poverty or ill luck). K M Gupta, in, A Temple for the Goddess of Anima (2002), mentions that off the old Calicut-Madras Trunk Road there is a village called Thacha natu-kara which has a temple dedicated to Jyestha: “Lakshmi is the goddess of persona and Jyeshta is the deity of anima.” Jyestha is also associated with kumbhi/pitcher and Nirrti in the Baudhayana Grhasutra. One is the symbol of fertility and the other of death. Sukumari Bhattacharya (1975) points out that the manual of iconography, Suprabhedagama, associates her with the crow, which in many parts of India, is still a symbol of dead ancestors.

Jyestha’s edging out from the dominant pantheon on the grounds of being old illumines the changing norms of the feminine, the symbology of colour, the significance of domesticity and even the changing landscape of agrarian rituals. Would Jyestha’s fate be different if she had been conceptualised as young, golden and beautiful?

***

Apsaras, iconised as always young and beautiful, are popularly thought of as dancers in Indra’s court. Etymologically, though, Monnier-Williams’s dictionary (1899) derives the word from “going in the waters or between the waters of the clouds”. The Rgveda also invokes them thus,

The Apsarases belonging to the sea, sitting within, have streamed toward Soma of inspired thought… (IX.78.3)

Water changes form, finds and feeds life in circularity. Age does not wither it (though human beings are now doing their best to run the world dry).

There are also personifications of apsaras in certain sections of the Rgveda. The apsara Urvashi is invoked as the mother of Vashistha (and Agastya):

And you are the descendant of Mitra and Varun.a, o Vasis.t.ha, born

from Urva?ī, from her mind, you formulator. (VII. 33,11).

A later portion of the Rgveda presents a dialogue between Urvashi and the mortal king Pururavas, which imbues female speech with agency. The dialogue begins in media res, as Urvashi is leaving her husband Pururavas, with whom she has a child, Ayu, to possibly join other apsaras. He asks:

Urva?ī: “What shall I do with this speech of yours? I have marched forth, like the foremost of the

dawns./ Purūravas—go off home again. I am as hard to attain as the wind.”

(Rgveda, X.95. 1-2)

Pururavas seeks to bring her under his sway as wife. Urvashi provides her own perspective and spurns his attempts to be “the king of my body,” to “pierce” her when she “did not seek it” (trih. sma māhnah. ?nathayo vaitasenota sma me ‘vyatyai pr.n.āsi | purūravo ‘nu te ketam āyam. rājā me vīra tanvas tad āsīh. || X. 95. 5). When Pururavas demands his son, Urvashi says, I will send it [=child] to you, that thing of yours that’s with us. Go away home. For you will not attain me, you fool. (X. 95. 13)

The ‘story’ has been variously retold and most famously in the Satapatha Brahmana (11.5.1.1-17) and Kalidasa’s Vikramorvasiyam. In both, conjugal love triumphs, the birth of the son is given greater prominence and curses replace Urvashi’s own desire for agency. Urvashi ages, one might say, in reverse. Perpetually flowing like water, the mother of sages, and refusing the narrow role of wife, Urvashi in later tradition is represented as being born from the thighs of the sages, Nara and Narayana (The Devi Bhagavat Purana, 4. 6. 33-35). She is made eternally beautiful but committed to dance to the tune of others. She whose name meant, to pervade and be widely extending.

***

In many parts of India, especially in the east, Sasthi is the patron deity of childbirth, infant mortality and welfare. The pauranik and epic traditions refer to Sasthi as the six Krttikas associated with the birth of Siva’s son, Karttikeya. In these narratives the emphasis is on the power of Siva’s semen rather than the nurturing provided by the female community. Paradoxically, Sasthi is also made Skanda-Karttikeya’s wife (Mahbharata, 3, 218). The shastraik dhyana mantra iconises Sasthi as a beautiful sixteen-year-old wife but the goddess lingers on in popular memory as an old woman: single, self-sufficient and often accompanied by her cats.

***

Chandi is a demon-slaying goddess. The Devi Mahatmya section of the Markan.deya-purana fuses her with other militant goddesses. The Harivamsha mentions her while invoking the composite mother-goddess such as Katyayani of the Katya tribe or Kausiki of the Kusikas, the mother-goddesses of Nishadas, Shabaras, Kiratas, Pulindas, etc. The extremely popular genre of Bengali performative poetic-compositions, the Chandi Mangalkavyas, from the 16th to the 18th century, also venerate her as burhi/old woman and she is often accompanied by her sisters-in-arms.

***

Ageing is organic. Inevitable. But attitudes to ageing are more socially constructed than is generally appreciated. These psychosocial orientations get embedded in the individual as much in the community. In negotiating these changes and challenges, goddesses present us with powerful images of old women even with gaunt bodies, sagging breasts and stomachs. They reveal the usage of old as labels, in contempt and in esteem. They illumine the price paid for shackled youthful beauty and sexual allure. And the importance of sisterhood.

(Views expressed are personal)

(This appeared in the print as 'Old Goddesses')