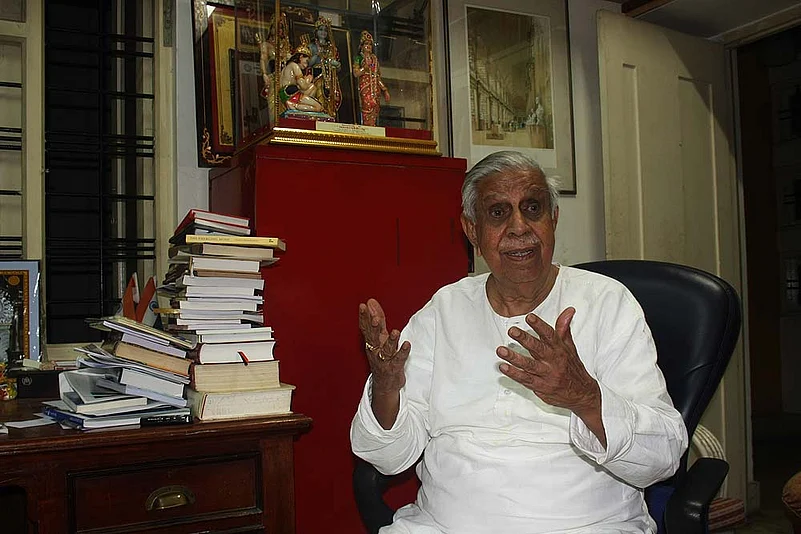

Former Chief Justice of India M.N. Venkatachaliah has since his retirement been associated with some of the country’s top institutes of higher learning.? And as we steer the world’s lar-gest youth population, he feels policymakers aren’t looking at the bigger picture. In a conversation at his home in Bangalore, Justice Venkatachaliah, now 87, outlines the need to create an environment of academic fervour. He’s equally at ease discussing law and science which he keenly follows, but the man who led the constitutional review committee refuses to be drawn into the debate over the National Judicial Appointments Com-mission. Excerpts from an interview with Ajay Sukumaran:

‘Academic Freedom Of A Harvard Or Yale Isn’t Allowed Here’

Former Chief Justice of India M.N. Venkatachaliah on the need to create an environment of academic fervour.

You were chancellor at Hyderabad University and NLSIU, Bangalore and pro-chancellor at Delhi University. What’s your take on the quality of professional education now?

There is a conscious effort at improvement, but it will take quite some time for us to reach world standards. I know in law, it’s been difficult to get excellent teachers. Good students who have done well in the universities go to corporate service or into practice, very few come to teaching. And teaching is a little difficult now. My father had a huge practice, he dropped it to be the first principal of Government Law College (Bangalore). People were astounded that he threw away a practice of that kind. Or take the case of American professor Walter Gellhorn who did so well. He was the law clerk of (Justice) Louis Brandeis. Though he had a very lucrative offer from a professional body, on the judge’s suggestion, he went to academic life. Such things don’t happen here. Those who do go, they cry. The peaks are high, the average not so. That’s the problem. Academic life is something totally different, the inspirations are different, the attractions are different.? Today, they feel as if they are some kind of employees, servants of either the government or of some capitalists who started these colleges. The academic freedom of a Yale or Harvard isn’t allowed here. It’s only in such conditions? that ideas blossom and creativity comes out.

Our stimulus for higher education in India is a reaction to the demand they perceive in the emerging scientific market. This is how they want to tailor readymade MBAs, CAs. Really, that academic fervour is not there. They are all manufactured for certain purposes, it’s just demand and supply. You place an order for 100 engineers, I manufacture them and give them. This is the philosophy and that’s where I have some reservations about the quality of higher education. The kind of regulations today is a rea-c-tion to problems.

Would you like to see more jurists go back to teaching?

Yes, of course. That’s where all the creative work is.

What needs to be done to encourage people to do that?

Respect for them...see, a professor works under a clerk in the education ministry and a vice-chancellor has to wait in the corridors to meet a secretary. No secretary comes and meets the vice-chancellor in the university. If there is a file to be cleared, you must go. It has simply made them clerks. And the way they are treated, and allow themselves to be treated... (laughs) I was on a number of boards to select vice-chancellors for central universities, I know what kind of funny things happen.

You entered the law practice in 1951 with a degree in science and then another in law. How do you view the rigour these days?

The typical legal practice of the old days is gone and today the kind of issues that come up in the interface of new biology and law are going to be mind-boggling. For example, you take a sip out of a cup of coffee and leave it at the table in the restaurant. A genetic trophy hunter will pick it up and a small touch of saliva clinging on the rim of that cup can give up your entire genetic makeup, your propensity for diseases, your existing diseases, your lifespan...he will have everything, and what’s the privacy part of it? How does it invade privacy, what is the law that can control it, what are the principles you will lay down?

Technology is something you have frequently spoken about in your talks....

The prediction is 10 years from now, all major decisions will be taken by artificial intelligence. Only 15 per cent of the world is technologically innovative, 50 per cent of the world absorbs or buys that technology and uses it, 35 per cent is technologically disconnected because they are priced out. So you can’t look at anything in isolation. Education or excellence in education, it depends on our scientific preparedness. Amartya Sen delivered this talk in 1997 on the foundation for scientific development and economic growth, what he calls ‘social preparedness’. The education of the age group between 15-19 will determine the country’s progress. India has a great demographic dividend in the sense our population between 15-20 is higher than China’s. How we have used it is another thing. For example, China has only 75 per cent of arable land compared to India but they grow more food. Post-harvest technologies are not developed in India at all. It requires a vast investment and vast network of roads. These are all very intertwined things. What we see is a sectoral view, a peephole kind of look at things. This is not possible anymore in civilisation. Higher education is inextricably intermixed with so many other factors.

In legal education, how have things changed in the last decade or so?

The philosophy of legal education has changed thanks to the pioneering work done by some good educationists who started NLSIU. The NLSIU is not only a metaphor for the quality and range of legal ideas but the philosophy of legal education...what it sho-uld serve, and how to transform con-stitutional promises into reality. This kind of new thinking is going on and I must tell you some of the educationists have had that bigger picture of the role of lawyer in society—not merely fighting a case but in educating people. Now, we are rediscovering Mauro Cappelletti (the Stanford professor who wrote seven volumes of Access to Justice) in the sense of the ultimate destiny or purpose of law. You must have awareness of rights, assertion of rights, access to justice.

Is there a need for more institutions of this kind?

Certainly, law is a metaphor for change, and bankers, students, policemen, magistrates, everybody must have awareness of the awesome responsibilities of living in a democratic polity. See, in the training or education system, there is no affirmative act-ion. Unless there is affirmative action, people’s empowerment will not take place. In my constitutional review com-m-ission books, I have mentioned the philosophy of talent schools. I’m worried, for another generation, what kind of beautiful world can we build for them. We don’t even think of it.

What would be your top concerns in this regard?

One is the importance of a comprehensive education. Second is preventive healthcare. Now, healthcare is not merely medical care, 72 per cent of all illness in this country can be avoided if you give them potable water. Then basic sanitation.

Speaking of the constitutional review commission, what are your thoughts about the National Judicial Appoin-tments Commission?

I don’t want to say anything.

What is your view on the debate over judicial overreach?

In areas of advancement of fundamental rights, basic freedoms and minimum standards of living, it is absolutely necessary. There is a beautiful collection by Philip Alston, Enforcing Human Rights Through Bills of Rights in which you find that activism in the area of human rights and fundamental freedoms is necessary. It is also necessary in carrying out the social philosophy of the constitution, social justice. And it’s also necessary in areas where you provide minimum requirements for a life to go on. But you go to more sophisticated areas, as judicial overreach, that becomes a slippery slope. In The Tempting of America by Prof (Robert Heron) Bork, he says in individual cases you go reach out to a person on the point of conscionability and human situation. Results are good but it develops a faint crack in the foundations of the constitution. A judge is acting where an executive officer should act. ‘Shift an electric pole from this place to that’—all this is an executive decision. ‘You can’t have transformers in the middle of the footpath, a train must come to a place at this point of time’—there are many judgements of this kind. Some of them are ego trips, erecting your prejudices into principles. This is where we fumble.

Which five books would you suggest for someone in the legal profession?

Holmes-Pollock Letters, Holmes-Laski Letters, the Human Development Reports of the UNDP, Raymond Kurzweil’s Fantastic Voyage and Professor Vilayanur Ramachandran’s The Emerging Mind. Just read Justice Frankfurter’s introduction to the Holmes-Laski Letters, it’s sheer poetry. And, you may add Jeffrey Sachs’s Common Wealth.