Master Of Floating

An unsatisfying book ignores the context, the contradictions and the persistence of Laloo Yadav

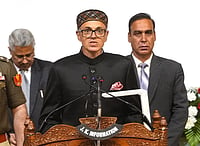

Some of the photographs in the book are delightful—an almost unrecognisably skinny Laloo posing with Rabri and children in front of the Taj, playing Holi, cooking and in a variety of characteristically provocative poses. Yet, the book—palpably a puff job for theUnion railway minister—is a waste of an opportunity to examine not just one of the most colourful figures in Indian politics but whose rise is also reflective of the huge social upheaval sweeping the country. Instead of bringing out a publicity brochure, the authors Neena and Shivnath Jha would have done their protagonist far more justice had they attempted a deeper and more objective appraisal.

Indeed, the many paradoxes that mark the evolution of Laloo Prasad are the same that make the growth of Indian democracy and electoral politics such a complex phenomenon. For instance, the amazing impact he made in Bihar despite lacking either ideological substance or organisational skill and that too in a state where the idiom of radical backward caste politics was set by a genuine grassroots leader such as Karpoori Thakur in the 1970s. Perhaps more than any other leader, he has demonstrated the importance of showmanship and symbolism in day-to-day politics, thus hijacking the political agenda from his peers in the socialist movement in Bihar.

There is also the contradiction between Laloo’s claims to be the champion of the poor and downtrodden in one of the country’s most feudal and backward states and the stark reality of his own Yadav caste brethren and core electoral base being the real oppressors in the countryside. Similarly, his venal corruption, the murky deals struck with mafia dons and the crass nepotism in favouring relatives have mirrored the very privileged castes and classes he has scoffed at through his career. Just as his shambolic governance as chief minister directly and indirectly through wife Rabri Devi drove a few more nails in the coffin of Bihar already languishing under a series of incompetent and corrupt rulers from across the political spectrum.

Despite his growing marginalisation in Bihar, Laloo Prasad has still shown remarkable gumption in staying alive in national politics. He has surprised everyone by his successful stint at the helm of the railway ministry, which has returned unprecedented profits, and is now even hailed as a ‘management guru’.

The once virulently anti-Congress Lohiaite has also belied predictions that he would be a pain in the neck for the UPA by becoming its most reliable prop and actually enjoys a close personal rapport with Sonia Gandhi.

The manner in which the rustic radical has flourished in the Congress-led coalition and managed to gain acceptability from the intelligentsia underlines two things. The first is Laloo’s own compromise with the system, which has increasingly mellowed his earlier iconoclastic fire. At the same time, India’s political establishment shows an uncanny ability to include outsiders such as Laloo, who soon develop personal stakes in not rocking the boat too hard. To the Bihari leader’s credit, he has managed to orchestrate his sellout with good grace and, more importantly, a sense of humour. This makes him an instant hit with his audience, regardless of their class.

Unfortunately, none of these issues are at all addressed in the book, although there are occasional attempts by his publicists to place Laloo Prasad in his socio-political setting. These are however very scattered, further ruined by appalling sentence structures and a jerky narrative, interrupted at random by separate articles written by Mani Shankar Aiyar and Mohan Guruswamy.

Considering that there are so few biographies of the galaxy of interesting political personalities in India, it is a shame that when one does get written it turns out to be not the real thing.