If a pointer is to be put on when it was that the United States’ relations with its ‘non-NATO ally’ Pak-istan began unravelling in the Age of Terror, most observers would choose the dramatic raid on May 2, 2011 in Abbottabad that killed Al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden.

In Jail And In Court, They Defer To Americans

The Raymond Davis affair shows the uniqueness of US-Pakistan ties: distrustful, yet accommodating. Davis’s own weak account skirts the issues which roiled relations.

Twenty-five days after the raid, then US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visited Islamabad. The chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral ‘Mike’ Mullen, also flew in separately. It was a concerted attempt against heavy odds to level with the Pakistani leadership. Clinton warned that the relations had reached a “turning point”.

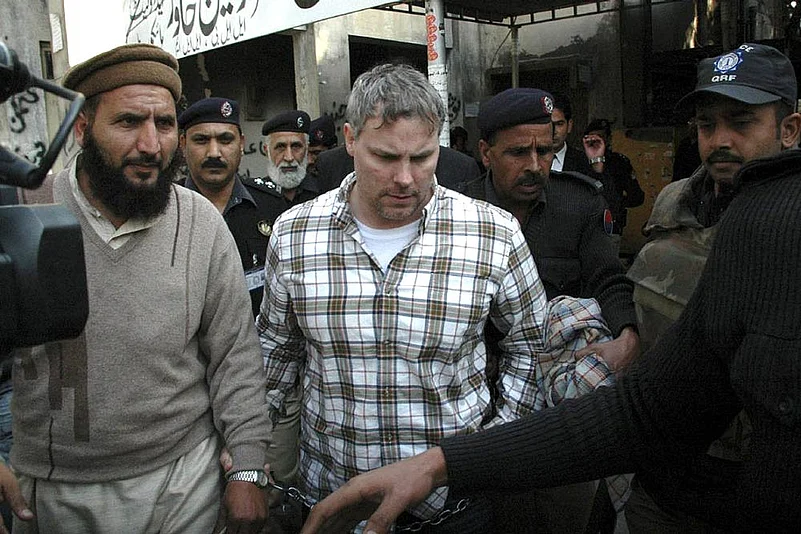

But a recently published book, The Con-tractor: How I Landed in a Pakistani Prison and Ignited a Diplomatic Crisis, helps rem-ind us that the ‘turning point’ had alr-eady been reached earlier. The book is a first-hand account by Raymond Davis, a former US Army soldier in the elite special forces and a contractor with the Central Intelligence Agency, on his murder of two young Pakistani men in cold blood on January 27, 2011 when they approached his car on a motorcycle, their guns drawn, at a traffic-congested intersection in dow-n--town Lahore.

Davis was detained by the police and was locked up in the infamous Kot Lakhpat prison in Lahore for nearly seven weeks. The Americans moved heaven and earth to get him released, but Pakistanis demanded to know his real identity and mission in Lahore, and a stalemate ensued. The episode underscored that there was little transparency in US-Pakistani ties at the working level.

But, going back even further, it was circa 2008 that the CIA began depending on drone attacks on militants in the tribal agencies of Pakistan. The CIA ceased to intimate the Inter-Services Intelligence in advance about the attacks, suspecting that the ISI might tip off targeted militants. The CIA instead began flooding Pakistan with dozens—or hundreds—of operatives like Davis, thanks to the inc-redibly liberal visa policy followed by the Pakistani embassy in Washington under its ‘pro-American’ ambassador Hussain Haqqani. The new focus was on the activities of militant groups such as Lashkar-e-Toiba, which were mentored by the ISI.

Davis was one of such CIA operatives who slipped in and out of Pakistan on covert assignment. Alas, his book is more like a prison diary and completely sidesteps the most intriguing things about him regarding his real work in Pakistan as a private military contractor hired by the CIA. But never mind, a great deal has been written about him from which we know so much more about him than what the book yields. When he drove out of the CIA ‘safe house’ on that fateful morning in January 2011, where was he heading? Was he keeping a secret rendezvous? Was he meeting a ‘source’? Indeed, was he undertaking a dangerous operation? According to Mark Mazzetti at the New York Times, “An assortment of bizarre paraphernalia was found (in Davis’s possession), including a black mask, approximately 100 bullets and a piece of cloth bearing an American flag. The camera inside Davis’s car contained photos of Pakistani military installations, taken surreptitiously.”

Davis claims he took a decision in split seconds to kill the two motorcycle riders. Were they familiar faces? One of them was involved in something like 50 criminal cases, but was never sentenced by a court--and in Pakistan it can happen only to a privileged fraternity who are a law unto themselves. At any rate, Pakistanis wildly gossiped about Davis, which in turn further fuelled the ‘anti--Americanism’ in the country.

‘Anti-Americanism’ is a double-edged sword in Pakistan. It provides the elite with the alibi to hunker down if there is US pressure. Yet, it also provides cover to transact business with Washington on the quiet. Davis’s was a classic case. The ISI probably suspected all along that he was a CIA operative. At one point, in the early phase, the then ISI head, Lt Gen. Ahmad Shuja Pasha, who was a rare spymaster in his reasonableness, travelled to Langley to meet his CIA counterpart Leon Panetta. But Panetta lied that the CIA had nothing to do with Davis. Pasha’s intention was to strike a deal and he ret-u-rned feeling disheartened that Panetta lied.

But then, President Barack Obama himself had referred to Davis as “our diplomat in Islamabad”. With hindsight, we now know why Panetta (and Obama) lied. The CIA was already following up on the intelligence regarding bin Laden’s house in Abbottabad and Pane-tta didn’t want to get entangled with Pasha in a secret deal just at that point.

For sure, Pasha let ‘anti-Americanism’ take over. Much as Americans fretted and fumed, Davis had to sit in the prison eating rice and chicken curry and doing push-ups. Soon, he was to go on trial, at which point, Washington became nervous, as Davis had to be somehow brought home before the SEAL Team Six swooped down on Abbottabad. Or else, the Pakistani military might just take revenge on him.

Washington finally decided to heed the consistent, sane advice by ambassador Cameron Munter from Islamabad to come clean on Davis and negotiate a deal. It goes to Pasha’s credit that he had no ego problem when Munter met him. But by that time, ‘anti-Americanism’ had cascaded and the mobs were demanding Davis’s execution. Pasha took a week to work out a deceptively simple solution: he simply had the court hearing Davis’s case to turn on its head and become a ‘Shariah court’. The ISI, in turn, made an offer to the grieving relatives of the two young men whom Davis had shot that they couldn’t refuse—$2.4 million in cash as ‘diyat’ (blood money). Pasha personally sat in the Shariah court room to ens-ure that there was no slip between the cup and the lip. Davis took an SUV from the Shariah court straight to the airport to a waiting Cessna aircraft, which spirited him away from Pakistan to a homecoming in America.

Of course, nothing of this thrilling story appears in Davis’s book, which is devoted largely to inane things. Curi-ously, Davis was never tortured. His captors in their “unipolar predicament” were all but deferential towards their American captive. Imagine if Davis were an Indian and was at the disposal of the ISI exclusively for seven weeks!

One sad day in Islamabad in 1992, at about 4.30 pm, upon receiving a phone call from the Pakistani foreign ministry, I went to pick up a senior diplomat in our Mission—no less than of counsellor’s rank—who was kidnapped by the Pakistani intelligence as he was leaving for work in the morning, right there on the blind alley leading out of his house. At the police station, I saw my senior colleague seated on a chair with a dazed look on his face, in virtual coma. My driver, a burly Jat ex-serviceman from Haryana, had to physically carry the counsellor to the flag car. And in the deep silence in the Merc as we drove to the chancery, he leaned to touch my hand and said, “Bhadran, when I saw you, I thought I was seeing God.” I silen-tly wept. During the seven hours in the cus-tody of his interrogators, an electrode was put on him to break him to extr-act information. Davis was plain lucky that he was born an American.

Davis’s story helps us gauge the faultlines in the US-Pakistan relationship. It has always been an unequal relationship, but the tail somehow mastered over time the fine art of wagging the dog. The big question is, what will the Pakistani elites do if the Americans wield a really big stick in the troubled times ahead. Pak-istanis think they have a ‘China option’. I am not so sure. But then, the Davis affair flags that the Pakistani and American elites are made for each other. They’re a match made in heaven, perhaps?

(The writer is a former diplomat.)