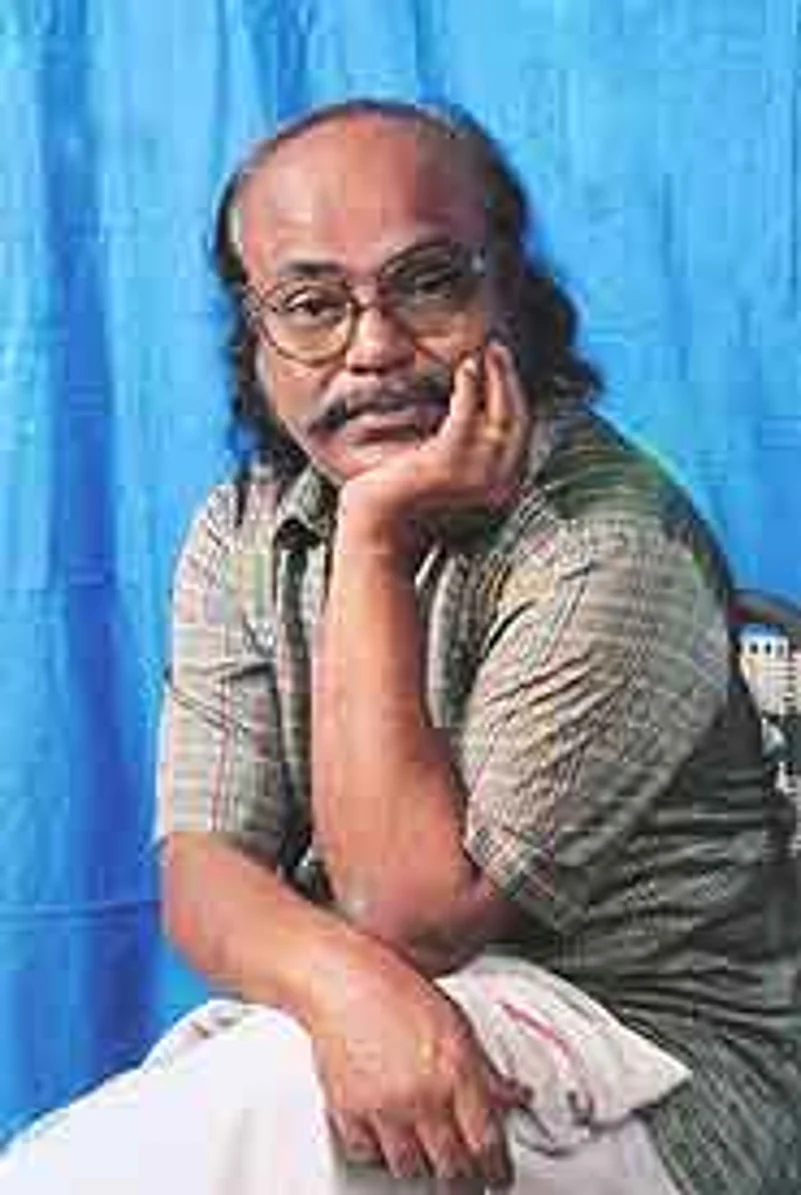

DandapaniJayakanthan, 71, was pushing forty when he received the Sahitya Akademi awardfor in 1972--quite unusual, as Tamil writers are deemed eligible only after thehair turns grey. Since then he has not missed a single honour due to any Tamilwriter. The one award that eluded him is now his: the Jnanpith. Jayakanthan’soeuvre is staggering. Some forty novels, novellas, hundreds of essays, filmscripts, columns. But he is predominantly known for his hundred and fifty oddstories.

Courting Controversy

Harsh critics may feel that being loud, argumentative and shrill is not the best route to literary acceptance. But the Jnanpith puts paid to that, and as the man says, it is 'not a recognition, but an endorsement'.

Thisschool dropout, born in Manjakuppam, Cuddalore district, in northern Tamil Nadu,began his life as a volunteer in the undivided Communist Party of India,distributing clandestine pamphlets at street corners when the party wasunderground. Little wonder then that despite his many volte-faces andembarrassing public statements Jayakanthan continues to be adored by most of thecommunists.

Jayakanthanpublished his first stories when he was barely in his teens in leftist journalssuch as Samaran and Saraswathi. Following the pioneeringPudumaippithan (1906–1948), he wrote stark and evocative portrayals of urban,lower-class life. For the first time rickshaw pullers, pressmen, prostitutes andfootloose labourers were convincingly and empathetically portrayed in Tamilfiction. Who can forget the pressman of Treadle who prints marriageinvitations but cannot himself marry. If his subaltern characters shockedreaders, his bold depiction of their sexuality evoked stronger opposition.Realising that nothing pays more than controversy, Jayakanthan has alwaysassiduously courted it.

Thephilistine Tamil popular press sensed the ready salability in Jayakanthan’sshock strategy and for the first time began to feature serious writing. Whenliterary writing in Tamil was getting ghettoised in the little magazines,Jayakanthan made deft use of this space and wrote with little inhibition. As thepopular weekly Ananda Vikatan became the vehicle of his writings,Jayakanthan’s protagonists also changed. Leaving the subalterns behind, hedealt with urban middle-class Brahmin life and explored themes such as Oedipuscomplex, premarital sex and notions of privacy and individualism. Fewwriters—Brahmins not excepted—have captured the Brahmin dialect as well asthis non-Brahmin writer.

Jayakanthansoon graduated from short stories to novels. Parisukku Po (Go to Paris!),Sila Nerangalil Sila Manithargal (Some People On Some Occasions, whichwon him the Sahitya Akademi award), Oru Manithan, Oru Veedu, Oru Ulagam(A Man, A Home, A World) betray similar concerns: an individual at odds with aputatively hostile society. For a generation between the late 1950s and theearly 1970s not a year passed without one of Jayakanthan’s writings being inthe news, seriously debated and discussed in the Tamil public sphere. It isdifficult to imagine today the furore caused by the short story Agni Pravesamin which an orthodox mother, without any moralising, exonerates her seduceddaughter. Jayakanthan’s women are strong and wilful even if they often speakhis words rather than their own.

IfJayakanthan is a celebrity despite ceasing to write for two decades now, he hasfrom the very beginning of his literary career been in active public lifedabbling in filmmaking, politics and journalism. Unnai Pol Oruvan, a filmhe made based on his own novel, inaugurated in a sense the ‘art’ film inTamil and went on to win a national award (1965). Taken along with his strongviews on commercial Tamil cinema and the star cult, especially surrounding M.G.Ramachandran, Jayakanthan’s forays into filmmaking and scripting offered theonly alternative cinema in Tamil. His negative views on Tamil cinema largelystemmed from his adversarial position vis-à-vis Tamil identity politics and theDravidian movement.

Alongwith K. Balathandayutham, the stalwart of the CPI in Tamilnadu, Jayakanthancampaigned consistently against the DMK from the 1960s and once even took onPeriyar E.V. Ramasamy who smilingly acknowledged the young man’s diatribe.Representing a stream within the Indian left movement that lays great faith inthe national bourgeoisie, he was closely associated with Kamaraj, defended theEmergency, legitimised the IPKF presence in Sri Lanka, and most recently argued in favour of the Jayalalithagovernment’s anti-conversion law. A good orator, his public positions arefrequently defined by his imagined rivals. His statement, made ahead of theEmergency—‘A Mahabharata war is now on in Indian politics. I’ve sworn thatI shall not take arms in this war. But I will be the charioteer’—reveals asmuch about his politics as his swagger.

Tohis credit, Jayakanthan stopped writing fiction when he felt that he had ceasedto be creative. He switched to writing columns, his powerful but humourlessprose ideally fitting the task. Voicing politically incorrect statements haskept Jayakanthan in the limelight. After a brief visit to the US some years ago, he called it a socialist state. If he wrotethe novel Jaya Jaya Sankara in the 1970s to extol the late centenarianSankaracharya as the epitome of nobility and a fitting rebuttal to atheism, hismost recent Hara Hara Sankara – in a virtually unrecognisable genre –is an unabashed apology for the present Sankaracharya.

Discardingthe white kurta, for long the uniform of Tamil writers, he wore fashionableclothes and insisted on posing for pictures with his smoking pipe peeping out ofhis twirled moustache. In a society where writers have been seen as onlysupplicants, Jayakanthan—who once advocated the use of ganja for getting anatural, chemicals-free high—created a new persona for the writer.

Generationsof Tamil readers and writers were indeed raised on reading Jayakanthan’sworks; but the present generation may see him more as a meteor than a star inthe literary firmament. Some harsher critics feel that being loud, argumentativeand shrill is not the best route to literary acceptance. If talking through thecharacters with ubiquitous exclamation marks was not enough, Jayakanthandelivered long homilies in his prefaces. Prapanjan, the Tamil writer, reviewinghis collected stories, likened them to ‘continuously listening to a publicmeeting from morning to evening’.

Jayakanthanhas been even more ill-served by translation. Though stories abound about hissuccess in Russian translation, translations into English (by A.A. Hakim, K.Diraviam, et al), perhaps because they predate the present boom in Indianliterature in translation, have failed to leave a mark.

ThisJnanpith is belated, at least by two decades. But it certainly helps erasememories of the blot created by the only other Jnanpith for Tamil (1975) forAkhilan’s mediocre Chithirappavai. The path has now been cleared forother deserving Tamil writers—Ki. Rajanarayanan, Sundara Ramaswamy,Ashokamitran. But to let Jayakanthan have the last word: the award is ‘not arecognition, but an endorsement’.

A.R.Venkatachalapathy is a historian and Tamil writer

- Previous Story

Review of Delhi Heritage Top 10 Forts by Vikramjit Singh Rooprai: Bastions?Of?History

Review of Delhi Heritage Top 10 Forts by Vikramjit Singh Rooprai: Bastions?Of?History - Next Story