The satirical magazine Private Eye has a standard response to celebrity obituaries. When someone famous like film dir-ector Bernardo Bertolucci, dies, the magazine publishes a first-person piece headlined ‘The Bertolucci who knew me’, poking fun at writers who use the opportunity to write as much about themselves as about the person who died.

Hall Of Refracted Truths

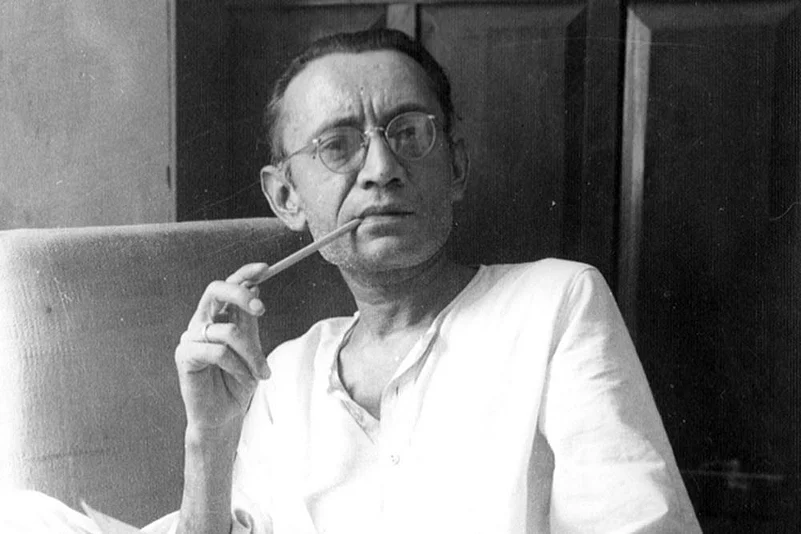

Like his coruscatingly brilliant stories, Manto was quirky, unpredictable, made of hard and soft edges. These essays, by his literary friends, confirm his genius.

This book has been written in the same vein. Saadat Hasan Manto was a remarkable man. He was not particularly literate (he left Aligarh Muslim University without a degree, having failed in, of all subjects, Urdu) or even well read. He was a Kashmiri who was raised in Punjab and moved to Bombay in his early 20s and began writing film scripts. At this he was not particularly good. There are no films that one can name today which he wrote, for they made little impact. The other thing he wrote were short stories. At this he is magical.

One way to test his greatness is to examine his relevance. Of his contemporary writers, almost none is read today, including the biggest name of the time, Munshi Premchand. His work is not relevant to the India of 2018. Manto’s is. That is why his work is still performed on stage, why there are movies on him and why, to return to the work at hand, there are books about people who knew him.

Manto Saheb: Friends and Enemies and the Great Maverick is a series of ess-ays, 15 in all, from people who were familiar with Manto. The best essays are four: the opening one by Manto himself, one by Ali Sardar Jafri (whom, in a Private Eye aside, I should mention that I knew), by Ismat Chughtai, who probably knew Manto best and one by his daughter Nuzhat, who probably knew him least, being only seven when Manto died.

Some of the other essays are not easy reading. The longest one, 70 pages, by Upendranath Ashk, is particularly tiresome. It has some interesting details about Manto, but it is made tedious by constant self-reference. It is not objective—nor, to be fair, is it meant to be, given its title: Manto, My Enemy—and not of particularly high quality.

The essay by Manto on himself is breezy and he probably wrote it in an hour or two. He writes in the first person but refers to ‘Manto’ in the third person. Called Manto’s Twin, the essay is disarming because the writer takes himself so lightly. He writes: “He is poorly educated, in the sense that he has never studied Marx; neither has he ever set eyes on any of Freud’s works; and he knows Hegel only by name.” He adds: “People should attain knowledge only through their experience.” Readers of Manto will know that this quality of his, to observe and record what he sees around him, is the standout feature of his writing.

Ali Sardar Jafri’s piece is a takedown of Manto from the perspective of a highly literate and ideological writer. It is a brilliant polemic. Sample this: “Manto could smash society to smithereens and scatter its remains far and wide. However, he could neither reconstruct it nor design a new costume to cover its nudity…. After 1940, he constructed his own yardstick for judging the success of his stories: the more controversy and uproar his stories generated, the more successful they were.” And also: “Manto, unlike Rajinder Singh Bedi, could not penetrate the hearts of his sad, dejected characters and provide evidence of the sincerity of the human heart.” But Jafri also says this: “From the perspective of art, Manto was unique and unparalleled. There was nobody like him. No other writer had the ability to create the impact that Manto could with the simplicity, dexterity and perspicacity of his language…he could flesh out a character in a couple of words.”

This is the best criticism of Manto I have ever read. Chughtai describes Manto as through a movie camera. She brings him and his movements to life: “He concea-led his troubles as if they were his failures”. Nuzhat Ars-had (Manto’s daughter) in her two---page piece opens with this devastating paragraph: “Abba pas-sed away in 1955. I was just seven at the time. My elder sister was nine and the youngest was five. It is self-evident that we were not old eno-ugh to be either influenced by our father or remember much about him. None of us were fond of reading or writing—something that became a source of satisfaction to my mother. Our mother’s opinion was unambiguous: It is better for people not to write.”