'All That Breathes' is a film about universal brotherhood, told through the figures of two actual brothers, Nadeem and Saud, who run a bird hospital in Delhi. Former bodybuilders, the burly brothers (and their elfin assistant Salik) are gentle protagonists, compassionate, and even spiritual in their quest to save the majestic and vulnerable “non-veg” kites that hover over Delhi. The film resonates with the spiritual message of democracy, that everyone is the same, that all of us - humans and fauna - are made of the same stuff. Shaunak Sen’s film lyrically lays forth its political point that democratic India is a home to all citizens, including the ones declared as non-citizens by the ruling establishment. The film sends out its political message without didacticism, and equally importantly, with keen attention to form, while eschewing most of the tools that mark the standard documentary template. The film begins with a long, unending shot of a battalion of rats, giving the impression that rats have overtaken the city. One can interpret this in several ways. Has India been overcome by rodents? Or, do the images of rats and maggots in the film seek to remind us of fascist slurs against minorities, like the ones propagated by German Nazis and Rwandan Hutus?

Brotherhood In Shaunak Sen’s 'All That Breathes'

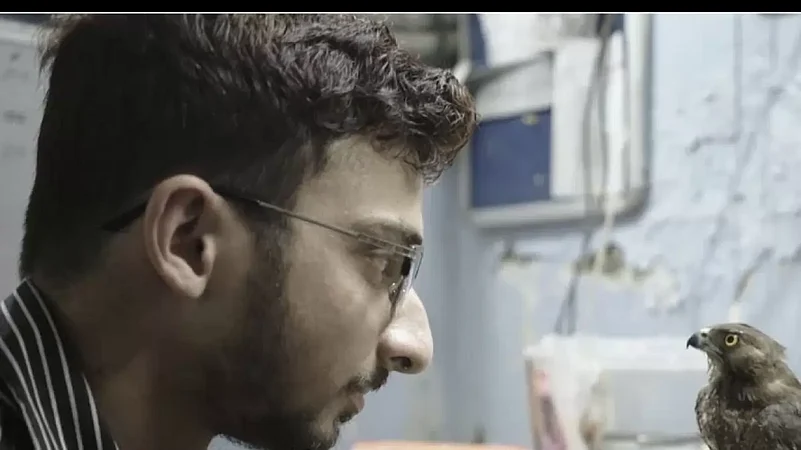

'All That Breathes' is a film about universal brotherhood, told through the figures of two actual brothers, Nadeem and Saud, who run a bird hospital in Delhi. Former bodybuilders, the burly brothers (and their elfin assistant Salik) are gentle protagonists, compassionate, and even spiritual in their quest to save the majestic and vulnerable “non-veg” kites that hover over Delhi.

Or, is the filmmaker giving an ecological, as well as a political, message of inclusivity - that rats and maggots too are made of the same stuff as everybody else - and thereby turning the fascist discourse on its head? Are there any good animals and bad animals, as fascists would like us to believe? Wriggling worms in stagnant water might seem repulsive and remind one of the animalistic metaphors fascists all over the world employ, but worms and insects are important to the ecology and the well-being of the planet and humans. Is the film in a way ‘claiming back’ the slurs used by fascist politicians? The planet is for all of us, as is democratic India where everyone is gasping for breath, Muslim or not, but especially Muslims. Indeed at times the brothers too come across as visually trapped in a cage themselves, a deliberate aesthetic conceit. The right wing brigade is never shown or referred to directly, but hangs all over the film much like the poisonous smog in Delhi, with its factories abundantly spewing venom.

The craft of the film is given welcome importance, compared to not just Sen’s debut film Cities of Sleep, but also the abundantly cliched documentary format that abounds so much in both Indian and international documentary spaces, with the average issue-based documentary being not more than a lugubrious ‘interview exercise'. All That Breathes includes quite a few evocative and lyrical shots, like the one in which Salik, sitting in a rickshaw, fishes out a squirrel from his pocket just after his mother has inquired about his safety. The encounter with the baby rodent becomes a tiny oasis of affectionate joy in a city becoming poisoned in more ways than one. But despite its lyrical and gentle rhythm, All That Breathes is an angry, seething film. Delhi is a feral city, with everybody living cheek by jowl with humans and their polluted mess. Yes, the feral mess is occasionally dotted with surreal, utopian shots of birds and animals. Migratory birds are surrounded by foamy waters; a turtle, fascinatingly out of place, crawls on a rubbish dump; a brilliantly lit up swamp is populated with scavenging pigs. These shots of ecological dystopia are given a utopian cinematographic feel and overlaid with accompanying music that evokes a sense of awe and wonderment like grand nature documentaries. But we do not forget the foamy waters and the gutters, like we cannot ignore the toxic fumes coming out of the symbolic chimneys of the ruling party’s hate spewing factories. Just like the birds and animals - whether they are growing extra limbs or tweeting louder to make themselves heard over Delhi’s traffic - the humans are also adapting to their new environment, that is, the hate filled politics and rhetoric of the political establishment. One of the brothers now wants to migrate abroad to more abundant pastures. Brotherhood is the whole point of the film. And the moving and evocative ending with one of the siblings repeating “Can you hear me?” while the image of the other brother has frozen due to a glitch, is a beautiful and moving end which doubles up as an indictment of the Hindu majority in India. Where are all the secular Hindus and why aren’t they standing up for their Muslim brethren?

The gentle and compassionate Muslim brothers in All That Breathes are nothing like the cliches that abound in contemporary unofficial, and nowadays even official, political discourse in India, which casts Muslims as unequivocally evil. But is the gentle and good Muslim a limiting iconography as well? There is nothing wrong with this iconography per se, though there is a risk of falling into a reductive, idealist (for the loony right) cliche of the well behaved and resigned Muslim. At the same time, those in the business of the moving image must understand that right now we do need more 'good Muslims' in our media to counter the hate. Much more than that, there ought to be more angry Hindu allies - angry with the establishment and with all political parties that are now flirting with soft Hindutva. Indian secularism is in peril and this film is an SOS plea - from one brother to another - to save the soul of India from this apocalypse. In his debut film Cities of Sleep, Sen indicts himself, as well as his largely Indian upper middle class audience, of being complicit in not really being there for the poor, but in only being interested in poverty porn. In All That Breathes, at a time when everything is in the name, Shaunak Sen steps up and insists that more Indians stop being mute spectators to the othering and demonising of Muslims that seems to be happening in contemporary India. Brotherhood is also what the director is urging, and setting an example by starting with himself. Indeed, the anger in the film comes from Sen himself and not directly from the brothers. We need angry Hindus, angry Muslims, angry Dalits, angry secular citizens across the multicultural spectrum of India to step up and overturn the factories of hate with counter narratives of our own.

Disclaimer: Divya Sachar is a filmmaker, photographer and writer. She also writes on the visual arts,

and is an educator in film. Views expressed?are?personal.

- Previous Story

Joker: Folie à Deux Review: Joaquin Phoenix and Lady Gaga Can’t Rescue a Flubbed-Experiment Sequel

Joker: Folie à Deux Review: Joaquin Phoenix and Lady Gaga Can’t Rescue a Flubbed-Experiment Sequel - Next Story