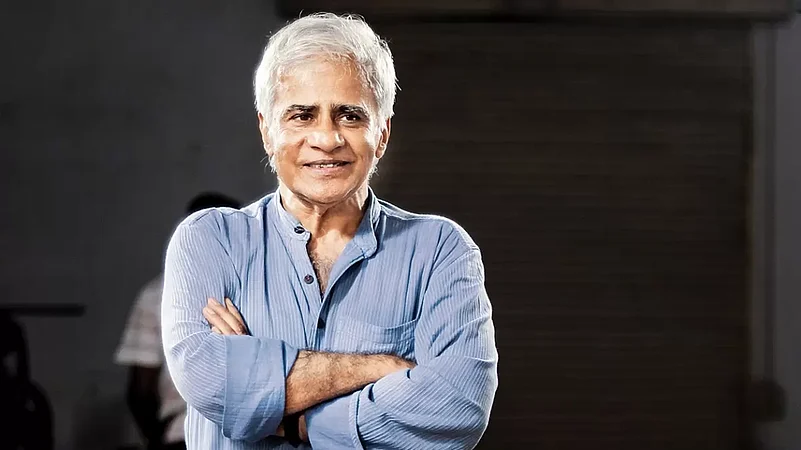

The demise of Vivan Sundaram has caused great sorrow to descend upon the artistic realm, leaving a gaping void in its wake. Sundaram, the legendary artist, was related to Umrao-Sher-Gil and Amrita Sher-Gil. He had been an illuminating presence in the art world for decades who had both the ability and audacity to bring together powerful political activism and provocative aesthetic experimentation, creating pieces that challenged all norms.

Artist, Rebel: Remembering Vivan Sundaram

Sundaram’s work and life were a blazing beacon of courage

After attending the Faculty of Fine Arts, MS University of Baroda, and studying at London’s ren-owned Slade School of Art, Sundaram was swept up in the whirlwind of the 1968 student protests, which guided him away from his traditional style into the realm of Pop Art—showing how an artist could also act as a revolutionary.

His presence in art circles was akin to a form of revolution; his rebelliousness was celeb-rated and his acumen to use art as a medium to express dissent took no prisoners. He defiantly questioned the status quo, all the while clinging to his radical vision of artistic expression—a persp-e-ctive that held fast to the ideals of the October Revolution of 1917 and didn’t flinch, even when those dreams were crushed in 1968’s simmering turmoil.

Returning to India at a time of great political upheaval, Sundaram’s artwork had become more than merely creative expressions. There was a fervent impulse stirring in him, an urgent plea for justice and equality in the wake of Nehruvian socialism’s collapse, as a despotism loomed menacingly, threatening to obstruct democracy.

His works struck out against the injustice and inequality he saw around him. Rather than searching for a reactionary response, his work dug into colonial history and unearthed the economic injustice that had been imposed.

He longed to bridge the gap between the darker nations—a term popularised by Vijay Prashad—to highlight the shared experience of poverty suffered by the Third World. Sundaram highlighted the relation between capitalism and the nation-state and conceived an aesthetic of resistance against religious nationalism.

His works sought to comprehend the moral imp-lications of power and politics within the framework of societies and their unique historical contexts. He explored the inner workings of society and its relationship to ethical values in a bold, incisive way.

Sundaram, an early proponent of institutional critique in India and a true intellectual giant, was never one to shy away from the importance of criticality. The counter exhibition— ‘Six Who Declined to Show in the Triennale’—organised by Sundaram and his peers in 1978, was a powerful reminder of the need to reject institutionalised oppressive dictatorships.

His artwork was an eloquent and robust demonstration of his opposition to tyranny—looming figures that brought terror into the environment and our minds. His commitment to criticality was unsurpassed among his contemporaries. The tributes and eulogies written on his demise are filled with endearment that remembers him as a kind and gentle soul, yet they fail to mention his prowess in the battle of wits—the sharp intellectual adversary whom few could match.

As Amy Sims has noted, the responsibility of the 20th-century intellectual was established to be that of an adversary—to speak out against politics when it goes against ethical and civil liberties. It is during periods of deep despair that these intellectuals, like sentinels on a pitch-black night, will be called upon to illuminate the truth and protect society.? Such is the role of intellectuals in dark times as Karl Mannheim said, “watchmen in what otherwise would be a pitch-black night.”

Sundaram, with an audacious and penetrating intellect, dissected the tyrannical forces of his day. His razor-sharp analysis wasn’t reserved only for his adversaries; even his close comrades and peers were subject to his scrutiny. His persistent provocations, gentle nudges, and soft-spoken perceptive remarks made him a formidable intellectual adversary within the intellectual landscape of a post-critical era, where critical remarks took a back seat in favour of affable eulogies.

The principles of “agonistic pluralism” by Chantal Mouffe can be advantageous when attempting to understand Sundaram’s critical standpoint. This new form of thinking centres around the idea of having a dispute with another, an adversary, instead of an enemy (a strand of thought inspired by Maria Lind)—an animosity which is encountered in antagonistic relationships. To put it simply, adversaries are those who share common grounds but differ on the meaning and application of principles—differences so vast that they cannot be resolved through rational discourse.

Sundaram’s body of work was a daring exploration of the aesthetics of resistance and its potential to counter-hegemonic forces. He firmly believed that art can be utilised as an instrument for social change, and his works served as powerful indictments against oppressive systems.

Sundaram merged the tactics of political activism with aesthetic exploration, creating provocative pieces that encouraged a re-examination of entrenched inequalities.

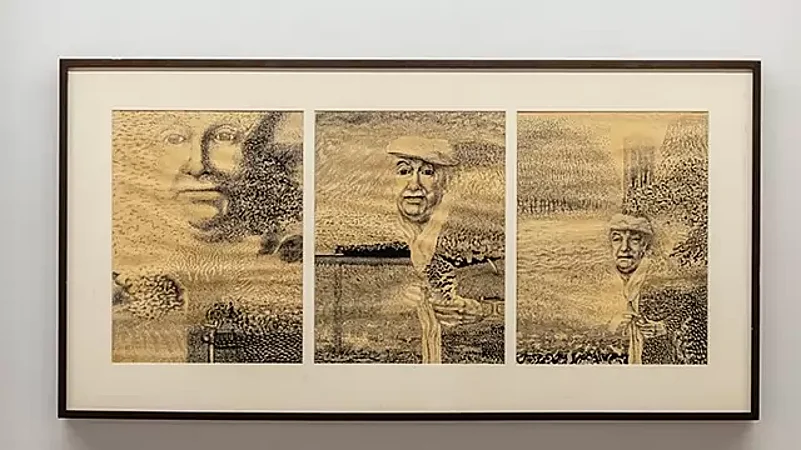

In many ways, his practice sought to subvert conventional discourses and push boundaries. His daring transition from painting and subsequent forays into the world of installation, montage and video art, his application of found objects, ready-mades, reinvention of images and exploration of archival materials are now legendary.

Sundaram vehemently contested the rigid control of traditional and bureaucratic administrative systems of art, believing that they stifled creativity. He espoused a devoted loyalty to Marxist principles with his artistic practice, instead of exploring a solitary and independent agenda. He, along with other artists, had to confront a drastic shift in the world around them with the brutal demolition of the Babri Masjid. Painting, he felt, could no longer adequately convey their new reality. Conceptual art and multimedia installations gave these creatives a platform to express their dissent and to comprehend how life had changed beyond recognition. They could form a chorus of voices that explored the intricate texture of living in the new fusion of capital with Hindutva politics.

His work highlighted the capacity to see beyond oppressive rules and embrace difference, challenging existing structures. He proposed a vision that transcended accepted boundaries and offered an alternative interpretation of reality. His impact on India’s cultural landscape was sizable. He set aside conventional wisdom, and the door opened to discourse on art, politics, philosophy, and culture in a manner unseen before.

As a prominent figure (Founding Trustee) of the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust (SAHMAT), he organised various events that addressed timely political issues. He gathered together cultural workers and intellectuals to create a powerful platform for discussion, debate and artistic expression. His various interventions, artworks, and lectures showed how meaningful fine art could be used as a vehicle for social reform and culture-wide change.

Sundaram’s questioning of existing norms generated a platform from which those whose opinions were usually excluded found an outlet—a true testament to his revolutionary impulse and unwavering dedication to the cause of progressiveness, even amid dark times.

History has shown that the very essence of creative expression is pushed to its limits in times of intense turmoil and upheaval. Curator Okwui Enwezor has noted this unsettling thought, whose observations leave a chilling reminder of how closely intertwined art and crisis can be. “Such crises,” Enwezor writes, “force reappraisals of conditions of production, re-evaluation of artistic work, and reconfiguration of the position of the artist in relation to economic, social and political institutions.” Amidst the chaos of dark times, Sundaram’s work and life were a blazing beacon of courage, bravely defying the autocratic ruling and exposing its unlawful authority.

The death of Sundaram is a great loss to the world of art. His passing rendered a yawning gulf in its wake. He left behind an incomparable legacy, that of an original thinker and activist. His artistic achievements were far more than mere objects of beauty; they constituted a statement of profound beliefs about our society and the world at large. His revolutionary works inspired both artists and activists to confront systemic injustices and fight for a fairer future. Sundaram’s unflinching artworks stand as powerful indictments of oppressive systems that hindered India’s secular and socialist values.

(This appeared in the print as "Artist, Rebel")

Premjish Achari is a Delhi-based writer and curator. He teaches art history and theory at Shiv Nadar University

- Previous Story

Joker: Folie à Deux Review: Joaquin Phoenix and Lady Gaga Can’t Rescue a Flubbed-Experiment Sequel

Joker: Folie à Deux Review: Joaquin Phoenix and Lady Gaga Can’t Rescue a Flubbed-Experiment Sequel - Next Story